And what did you hear, my blue-eyed son?

And what did you hear, my darling young one?

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’

I heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world

I heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’

I heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’…

–Bob Dylan, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

There’s always that guy, isn’t there? It’s ancient wisdom, passed down by drill sergeants and football coaches and small-town sheriffs the world over: there’s always someone – That Guy – who fucks it up for everyone.

We all know who it is, but we usually don’t speak up. When we do speak up, it’s because That Guy is a notable weakling, not a powerful bad dude. We know which side our milk toast is buttered on.

I was a private once, long before the deluded notion of “an army of one” was floated by misguided marketing hacks. Group punishment was how we rolled in Second Platoon. SFC Vince Tajalle was gonna grind in the notion of group effort, no matter how many guts he had to bust or heads he had to crack.

Fort Jackson, S.C. was where we learned every subtle nuance of the taste of red sand, one at a time and all together. Fort Jackson was where we learned lifelong lessons about That Guy.

People take the lessons differently. We naturally want to distance ourselves from T.G. He’s not a team player. He’s a weirdo, an outcast, maybe a little dangerous, or maybe just too weak to hang. We have all kinds of presumptions around That Guy: he’s just doing it to get attention; he’s selfish; he’s angry; he’s nuttier than we’ll ever be.

The first time we ran the obstacle course at Ft. Jackson – an exercise we were to repeat, according to SFC Tajalle, more than any BT platoon in the history of his man’s army – most of us made it through by the skin of our knuckles. We were wet and muddy and our arms were too tired to wipe the sweat out of our eyes – and two of us were missing, left behind out on the course somewhere.

Our drill sergeant fell us into formation where we stood, dripping and passing out and seeping small quantities of blood, locked up at the position of attention. He looked up at us through his narrowed, Guamaniac eyes.

“Who passed my obstacle course?” Nobody spoke. “I said, WHO passed my OBSTACLE COURSE?”

Smith, never the brightest bulb on the string, tentatively sounded off. “Uh, I did, Sergeant…?”

SFC Tajalle stalked over and pushed the brim of his campaign hat against the point of Smith’s chin. Most drills would bump their “round browns” into the bridge of a private’s nose or their eyebrows while they chewed ‘im out, but Sarn’t Tajalle was short enough that he had to improvise.

He addressed Smith more quietly than we’d ever heard him speak. His voice quivered with the barely restrained urge to stalk down each squad’s file, pausing to deliver a spinning roundhouse kick to the balls of every man assembled there.

“Did you make it through my course, Smith?”

“Sergeant, yes. I think I did, Sergeant.” By this point in our training, we were unsure of most everything except that we were due to be smoked at any moment.

Turned out, none of us had made it through the course until we all made it through. The good news was that we didn’t get smoked.

All we had to do was run the course again, picking up Anaya and Brothers along the way and making sure they made it through with us. That was how we spent our supper chow time. Third Platoon pulled our KP shift; in return, we got to pull fire guard for them.

Brothers was maybe 20 lbs. overweight and had just gotten too tired to hand-over-hand to the top of the 30-foot tower, but Anaya was That Guy for us. A pudgy career glue sniffer from Albuquerque, he just couldn’t grasp the concept of vaulting over a six-foot inclined wall. Most of us hopped up enough to get an elbow over, swung a leg and slid down the back side onto our feet, then pelted on past the screaming roundhat.

One of our guys was so graceful, fleet and tall that he could put two hands on top, leap and swing himself over with barely a broken stride. Anaya would blink behind his BCGs as he lumbered up to the wall and, encouraged by all present, bash straight into it and fall back on his butt – over, and over, and over. When we found him there on our second pass, he was still bouncing slowly off it like some bashed-in Roomba with its algorithms skewed. He wasn’t like us, but we picked him up and threw him over the wall, anyway.

“How do you catch a unique rabbit?,” my daughter used to ask when she was toddler age. “You ‘neak up on him!” She would giggle and giggle. Like most of us, I figure I’m fairly unique. Special snowflake fingerprint of DNA-level individuality, that’s me. I’m a military veteran and a peacenik; a liberal arts major and a businessman; a data plumber and a writer; a goy preparing to celebrate Passover; a gun-toting, gay rights-supporting libtard. I’m not like them; at the very least, I’ve worked pretty hard not to be That Guy.

It ain’t always easy. You could be standing next to That Guy and never know it until it’s unfashionably late. I was a young sergeant at Fort Stewart, GA when a private first class (name withheld because, well, he didn’t exactly plan to be That Guy; it was his patrimony) offered me a weekend ride up to the hills of NW Georgia to work on his truck and meet his dad, a retired sergeant major.

In accordance with the holy writ of army service (“eat when you can, sleep when you can, shit when you can”), I napped most of the way up, waking just in time to pull into a neatly kept property with a frame home, chicken coop, and work barn. When I saw a ’58 Chevy Apache up on blocks, I knew right away these were my people.

We passed a fine afternoon together. His parents fired up the Weber grill and fixed a handsome feed while we pulled apart his Ranger’s rear brakes, repacked the bearings and adjusted the shoes.

When the evening cooled and skeeters appeared, we retreated indoors to sit and talk over quiet Appalachian folk music on the radio. Clear peach moonshine appeared in a Ball jar and I don’t care what anyone says, there ain’t a grappa or slivovitz anywhere that can stand up to properly squoze Georgia ‘shine. Lights stayed off in the room to keep bugs on the porch, and my eyes were just starting to get heavy when racial politics oozed into the room like malignant kudzu.

“It ain’t like we got anything against ‘em, really,” the old sergeant major said as my eyes popped back open. “Just want them to be where they are, and us to be where we are, that’s all.

“You could join in, y’know.” He passed me a grainy, third-gen Xerox of the Ku Klux Klan recruitment oath. “Young blue-eyed sergeant like you.”

His towheaded soldier son smiled tentatively as I slipped it unsigned into my pocket and promised to think about it. I’m still thinking about it.

These are my people. They came right out and said so.

The synagogue congregants at Temple Beth Am aren’t really my people. At best, I might be construed as ger toshav, a righteous gentile, but in reality I’m mostly just some guy who pays the dues and reliably schleps his daughter to Hebrew school.

If I’m closely affiliated with anyone there, it’s probably the security guards, a small team of goyim military vets who post up outside the door to keep our tawdry, sporadic American pogroms at bay. A couple of years back, I strode through the temple door to drop off something for the kitchen and was halfway across the lobby when I heard Shawniece yell from the office.

“No! No! He’s a member!”

I turned to see one of our sturdy blonde security guards, jaw set and combat in his eye, heading for an intercept and takedown of the scruffy, middle-aged white guy in the Cabela’s gimme cap. Except for the better shave, he could have been my brother. Neither fish nor fowl, I couldn’t bother to be embarrassed. He and I may have chewed some of the same dirt in Georgia, or in Oklahoma, North Carolina, Korea, Kuwait, Iraq… just like Timothy McVeigh, who was also once a blue-eyed young sergeant.

These are my people.

I wish someone like our synagogue sentry had been standing guard in Kansas City last year. Maybe he would have stopped – or at least slowed – Frazier Glenn Cross before he shot up a pair of Jewish facilities.

John 11:35

A lifelong anti-Semite who believes white Christians are the only decent humans, Cross (AKA Glenn Miller) succeeded in murdering two white Methodists and a white Catholic. I’ve been to marriage counseling with a Catholic. I was once the president of my United Methodist Youth Fellowship group.

These are my people.

Cross served in the U.S. Army Special Operations Command, which means that the hate murderer and I (and our synagogue guard; the one with a big Ranger sticker pasted across the back window of his Hyundai) absolutely share some history.

Yeah, him too. Shit…

The day after we ran that obstacle course at Fort Jackson, all those years ago, we were out there again. And again. The third day, we ran it three times in a row. We were getting in prime shape, but the lesson hadn’t took. Anaya was making it through each time, though. We just kept chuckin’ him over that wall.

That evening, after mail call, our drill left us sitting in a circle while he talked. It wasn’t anywhere near good enough that we all made it back. We had to each make it, on our own and together, or it was like no one made it at all. I wouldn’t learn until decades later that it’s a concept straight outta the Talmud: Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.

Or his whole platoon. Our tough old drill sergeant’s eyes got far away when he talked about that. It was uncomfortable to see SFC Tajalle’s face wring up like that. My eyes wandered to the signet on his right shoulder, a combat patch from the 173rd Airborne “Sky Soldiers” in Vietnam.

Sundays were our day of rest… four hours’ rest, that is. We were offered the option of attending church (unpopular) or lying on the freshly buffed floor underneath our crisply made racks and inspecting the insides of our U.S.-issue eyelids. That Sunday, we selected “none of the above.”

Out on the range where we were unauthorized to be, four of us worked with Anaya until he discovered a way to get over the wall, all on his own in the company of his unwilling brothers. It was the first time I saw a light go on for him. It may have been the first feeble illum he’d experienced since whichever middle school year he’d embarked upon his tormented romance with Testor’s model cement.

Monday morning, after P.T. and breakfast, we double-timed to the obstacle course with SFC Tajalle cracking out cadence. “I wish all the lay-DEES… were holes in the ro-oad… and I was de DUMP TRUCK! I’d fill ‘em with m’lo-oad…”

Anaya went first that day. Nobody ran past him, and it was painful to watch. With every one of us yelling for him, Private Anaya surmounted every obstacle by himself and made us, officially, the slowest platoon that ever navigated that hell pit.

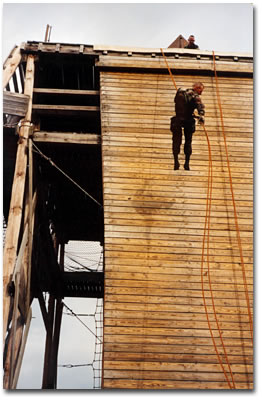

On no day did I ever have more fun in the army than on that morning. We finally got to relax atop Victory Tower, where we traversed single rope bridges and rappelled down the wooden sides. Anaya didn’t even fall off. He didn’t have to be That Guy, that day. We took him in.

A couple of years back, Tamarlan Tsarnaev became That Guy for Boston, where he was convinced no one had taken him in.

“I don’t have a single American friend,” he said before his pressure cooker went off. “I don’t understand them.”

For that young man, we were all That Guy, and he took out as many Americans as he could.

Muslims are like that, aren’t they? Always setting bombs and IEDs and shit. They make video entertainments out of cutting off infidel heads. Barbarians, every one… except the Iraqis to whom I’ve trusted my life, and would again. Those guys are alright.

I recall peering down from a 240-Bravo turret, into an Iraqi’s courtyard as our convoy ran the ridge road above. The mud walls surrounded a couple of half-restored pickups, up on blocks. Wondering whether the neighbors bitched about his yard art, I smiled into the dust.

From the turret of the vehicle following us, Walters (another young, blue-eyed sergeant) slung a piss bottle toward the ’58 Chevy Apache, throwing his arms up in victory when it splattered across the bed. I’d be lying if I told you I never laughed at that stuff.

There’s always That Guy. I’m trying not to be him, but I’ll always be his people and he’ll always be mine.

Yours, too.

Oh, who did you meet my blue-eyed son?

Who did you meet, my darling young one?

I met a young child beside a dead pony

I met a white man who walked a black dog

I met a young woman whose body was burning

I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow…

–ibid

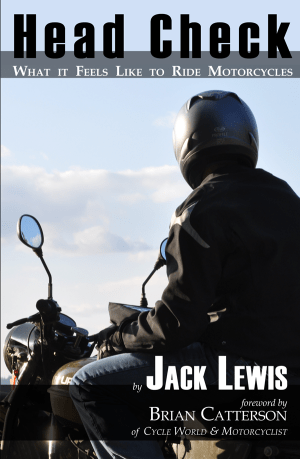

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Why does this bring tears to my eyes? Because it speaks of the soul of all of us.

On point, as usual.

Quality work. Jack’s always is. I’m uncomfortable being called to recognize that a lot of Those Guys are in fact My People and now control much of my government. Guess I need this attitude adjustment. It going to take some time. I’ll ‘neak up on it.

“True terror,” Kurt Vonnegut once said, “is to wake up one morning and discover that your high school class is running the country.”

Expecting every one of a group to be the same is as dumb as evading the fact that groups do have certain cultural tendencies. I lived, ate and hunted with and against the Vietnamese some time ago. Some were honorable men defending their homes and families. Some were murderous bastards who were a blight on the entire species. There were a lot fewer of the later working with us but neither side was 100% pure.

We expect more of our own “kind” because we DO have higher standards but few of us live up to them all the time. The question is what you do when you or those who are your brothers crew up. Nihilism isn’t an answer it’s an evasion.

SFC Tajalle, left an indelible mark on me as a soldier, for I was a squad leader in 2 platoon, E-9 2. Summer of 1982.