I limped over to my lathe and cut a bowl for her. It’s not my best work. It betrays tool marks. The walls are too thick.

I rushed it.

At one point, I caught a fingernail gouge hard enough to snap clean through its shank of entirely decent Chinese steel. How that clumsy instant didn’t blow everything apart defies my understanding. That was a painful catch.

I started with a good-sized burl. Punky and stone-hard by turns, the staunch resistance of surly, swirled cherrywood was intermittently betrayed by soft pockets of disease.

It’s riven with rot. That’s the nature of this material, hacked off the side of a tree that fell in a friend’s Lake Forest Park yard. Burl is less wood than it’s a model of visible disease, a tumor in the bark heralding its host’s demise. If not from crown gall then by wind or by insects, root-crushing vehicle weight, or the murderous rip of a chainsaw like the one I used to disarticulate and flitch the corpse of a giant fruitwood. Burl isn’t death’s enforcer, only its augury.

Death is grown in the grain.

Now that it’s skinnied down into a bowl, I can only hope it will hold together. As an offering, it misses my mother’s occasion. Cloaked in anti-viral practices, my family hasn’t been traveling. Not even to home state Oregon. Not even for Mom’s 83rd birthday.

She fell recently, bony butt down, and fractured her spine. She’d hoped it would hold together longer. We all had, of course. For my mother’s birthday, I diverted a hospital-grade cushion out of the Amazon torrent of consumer goods, and called to reassure her that spines heal.

They mostly do, sometimes. Depends on how hard you break one, how often, and in how many places. Depends, also, on how much time you have to knit. There will be pain. It will last for a time.

Perhaps for the rest of your time, I do not say.

With time and care and good fortune and exercise, my own spine healed. I walk slowly, sometimes with a stick, and I drop things – chisels, leash ends, dishes – when I lean slightly, but mostly only fall down to the left and not too often. Like my fingernail gouge, I’m shorter than I was, and reground to a less aggressive profile.

In a few minutes, we’ll toss our little red bag into our little blue station wagon and drive south to visit Mom. Because of the times we occupy, we’ll stash cloth masks in the car, avoid public restrooms, and graze out of boxes, bags, and bottles.

After visiting a while, we’ll turn west and chase the sunset of manifest destiny toward the last coast of America, where Mom maintains a small, cedar cabin just a few miles south of Lewis & Clark’s final outpost, and spend the night there.

On each visit, we putter at routine cabin chores. My sister and her long-term guy visited recently to hack away the blackberry jungle and air out the place, and I’m grateful. We’ll do less. Probably rub a little walnut oil into things, and scrub off the leather sofa if it’s started to mildew again. Once the roof leaked over it a couple of years ago, the spores of its eventual green fate became as entrenched as burls battened to a cherry bole.

Three items that often need oiling down at the cabin (“down” because it’s south, “down” because we drop through coastal mountains to the big water: down) are rudimentary bowls. I shaped those simple bowls some four and a half decades ago in seventh-grade shop class, at the school I attended from kindergarten through the eighth grade, mounted to face plates with brown paper and glue. Every iteration I made as a child required a base at least as wide as the single, available faceplate.

These days, on the rare occasions when I belly up to the lathe, I pinch a woodworm screw into my Nova chuck, bore the blank and spin it on. I form the blank’s external shape from the outside in, then cut a chuck foot into its exposed bottom with a notched chisel to form a reverse dovetail. Finally, I replace the woodworm screw with expanding jaws and flip over the now balanced, rounded blank to start on hollowing.

That’s where the trick is. Hollowing forms requires patient athleticism married to a half-blind rooting after possibility. The less sound the stock, the more elusive its promise. Like a truffle hog I dig, sneezing and squinting, into the revelations of fungi.

It hurts now. Most things do. Cost of doing business.

The hardest bit is leaning out over the lathe ways, head jammed halfway under an overhanging garage cabinet because we use what space we have, bending across a whirling blank to direct a chisel backward for the hollowing. My feet find every slippery shaving as I cantilever my weight sideways. My hands go clampy and tingle when I twist my body’s wiring harness, but these are the best days remaining in my run downward toward the sea and I must use them well before the thinning is complete.

No refunds for time lost. The bowl doesn’t get refilled.

Elbowing the pointed live center because I didn’t back the tailstock out far enough made me jump and I caught my gouge hard, threatening an explosion into flying fragments and vivid curses. With a ring like a blacksmith’s hammer, the chisel shank snapped and flew away, huddling under the lathe bench alongside my shattered serenity.

I’m not patient enough for this curious wood.

Everything depends on the hollowing, and it must be done slowly. How much can be excavated from the core and slung out of view, leaving just enough surface to hold everything together? Never enough until, episodically and suddenly, it’s too much.

This meditation consists in slowly, patiently thinning the walls with practiced swipes, the gleaming tip rising through curling ribbons of wood swarf to leave nothing of our passage but an air-weight form delineating the barrier between what is held and what is spilled. Naively presuming the extended focus of a Zen archer manning a machine gun, the closest possible approach to the ideal occurs seconds before explosion.

That’s when you stop, or lose. Without a monk’s patience, you will literally blow it – but short of heedless courage, you never get all the way there and I didn’t, not this time. Desperate for a tangible offering, I rushed it. This particular chance may not come ‘round again. I couldn’t risk exploding it.

I’ve blown through enough of them. Mom knows better than anyone that I’m sharp-edged, clumsy, and myopic; that I get snagged into sudden violence, and break my tools. Long before I did, she perceived that I wasn’t – could never be – the flower-sniffing Miura bull that I remember idolizing from a children’s story. She saw the death in my grain years before it emerged, inexorable as seasons, in her own.

In her story, it comes from my father but no matter the source, I own it now.

There exists a moment of balance perpetually wreathed in mystery, fragile and unsustainable, and I chase its asymptotic promise like my dog chases cottontails. We both know the prize will zig, with lightning alacrity, just before we can fasten our jaws around it but once that moment of “almost” happens it must exist, on some timeline, forever. Our near-triumph may be scrubbed out of memory and ignored by history but, equally with our sins, can never absent itself from our own, terminally enfolding reality.

Such flickers of grace exist in the oft-cited, paradoxical state of one’s education, in that their very evanescence assures (as someone once assured you, or you them, with avuncular confidence) that “no one can take that away.” The claim is as inane as observing that no one can “take away” the dawn.

Every sunrise died as it emerged, doomed by a decaying orbit nearly eternal but cycling brighter, hotter, and faster than our own spans; spinning faster than we can safely put a tool to it; a timeline of emergence and dissipation shorter and quicker than the life of a big, fragile dog or even the aforementioned rabbit’s fast-fused existence as a meal with feet.

Still we chase it, beyond the horizon to wherever it leads.

Her hips are going now; her spine as unreliable as my own. The other day, she stumbled against a school building and was marooned, hind paw raised, for 20 minutes while I dithered over how to tote home a 115-lb. dog. If my wife hadn’t fetched the blue wagon we might still be there, quietly negotiating the issue while I rubbed her legs and she looked a brown-eyed question at me.

The answer was no, sweetie. Not anymore.

I’m sorry.

Still, we chase that moment like junkies stumbling after crack, my old bitch and I. Ignoring the rot and snarl that will one day blow apart every flying shard of our plans, we pursue that fugacious high with the callow confidence of new lovers. We smell the spores of our demise undismayed, for she and I both know that the craziest grain compounds the beauty of hard and soft. Our moments turn back on, fold over, and repeat themselves, but the cutting edge of this moment remains the only time that is. Every curl hissed away from that ephemerum consigns itself to the fossil record, there to await expert misinterpretation.

Humans treasure the old, increasingly as we age. Neandertal graffiti grows priceless through antiquity, not skill. Leaving our tiny tracks like steps beaten into stone cliffs, we smile at the wonder of future humans. We build a place to build, and call it “shop.” We buy and modify and maintain and repair elaborate devices, then address that machinery with sharp, simple tools that we hope can somehow carve rational sense out of disappearing time, all to help us kiss infinity with enough courage and delicacy to cut away our own, tiny curl.

To leave that record for someone to read, as though it were somehow more interesting to future scholarship than a busted tool end rolled under our bench.

Hover your hand over the power switch and realize that all the moment demands is a little technique, some encouragement from a grown-up and the blind, stupid faith to push a weapons-grade toad stabber into several pounds of irregular wood spinning fast enough to blur. To seek, like racers and soldiers, the exhilaration of annihilation barely dodged. To keen, like thralls and lovers, for someone’s approval of our momentary cleverness.

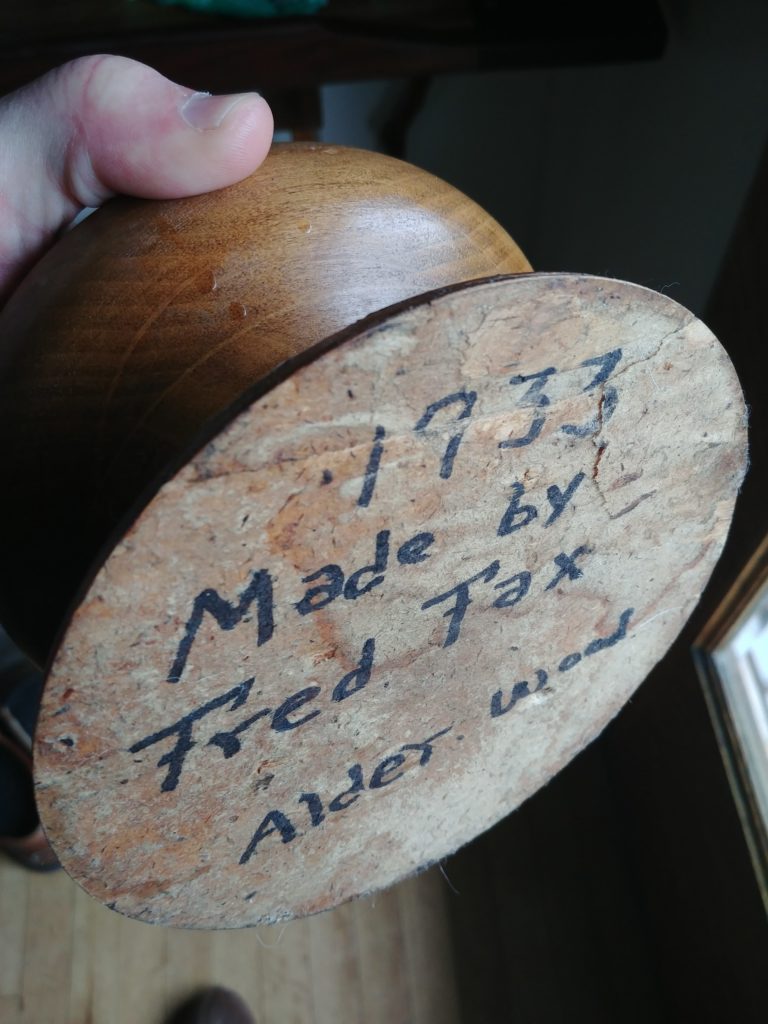

My great uncle Fred pursued this craft in his own time. Our household key dish is Fred’s work, composed wide-footed on a faceplate in one pass without flipping, four years before my mother was born. The moment outlived Fred and I looted his work, along with a hand-forged iron pin from the barn door, when the death of his sister-in-law passed the ancestral wheat ranch into strangers’ hands, for good. The old place grows things again as it once did and still must: soft white wheat, rye, and stands of lupine and balsamroot along the hedgerows where combines and disc plows can’t yet reach.

Life is grown in that grain.

I wear a full mask at the lathe now, and I’m glad for it because I took some sharp chunks to the face back then, working in the daylight basement of an elementary school built ten years before Fred put skew to alder. I only have one friend left to laugh with about all those bowls I blew up – usually the ones I rushed, and I used to rush everything – but the few I completed possess virtues unavailable to this odd piece. The bowls that hold my childhood are shaped into stolidly useful profiles from undiseased, vertical-grain mahogany and walnut stock: wood that’s hard to find these days. Expensive reminders of bygone times but I never paid more than a dollar eighty-five for a blank back in my school days, when those were commodities of unrecognized glory rather than guilty accusations of heedless indulgence.

Those old giant forests, masters of wind and makers of weather, base populations for ecosystems beyond our ken, are gone now. Their final stands are reserved for the wealthy few, but adaptable humans have persuaded ourselves of the beauty found in rotted remnants.

Fitting out a shop of my own imbued no additional grace. Impatience punishes me. Belying the low hours on my English lathe are a cleanly broken tool rest, and now this chisel. Decades back when I learned, if not skill, then at least fascination with this recondite practice, no fingernail gouges existed.

I’m still coming to terms with these outils difficiles. Roll one wrong and the catch is blindingly quick and cruelly severe. They’re a challenge to sharpen, but I have better resources than public school offered: a half-speed grinder turning friable white wheels, H.S.S. tooling that’s slower to burn, and a Wolverine jig to shepherd my tools toward consistent, gleamingly honed tips.

My other refinements are begrudging patience with the process and a smidgen of forgiveness for my own weakness and errors. These days, I work slowly around the hard spots.

Not that they’ve stopped surprising me. Just ask my shorty fingernail gouge.

Of course it’s all as pointless as dervish dance. Nobody needs a nut dish laboriously harvested and dried, shaped and cut, yet still riven with soft spots portending failure. My offering to Mom wasn’t patiently cut from evenly grown alder by a trained craftsman, but bullied into shape by an angry amateur from a beautiful piece of death that slammed to earth like a god’s hammer and was contentedly softening into earthworm poop at the moment I stole it away from nature’s process.

It’s structurally inferior to a fifty-cent china bowl from Goodwill. Fred’s bowl will outlast both ends of my mother’s span, but her gift will rot to dust — just another piece of wasted firewood — eons before that Goodwill ashtray is chipped out of our ridgetop hardpan and held exultantly aloft by an archaeology intern (probably one closely related to cockroaches).

There’s no way to predict how Mom will receive it. We don’t talk the way we did. Plenty of reasons for that, many involving my impatience. But maybe she’ll tell me another story or two, and maybe I’ll just listen.

Mom’s stories are simple truth. She’ll brook no editing by Jackie-come-latelys. In her questing memory, each tale is hewn from straight-grain heartwood of perfect integrity. Mom refines her narrative around strong throughlines. Contrary grain and visible decay are sliced away from each retelling, hollowed finer with every turn. In her remembrance, no member of her brood was ever thrashed or broken or jailed; her pets were clean and obedient; enemies who were not acknowledged then may not be spoken of now. She’s neither disappointed by rot, nor startled by abrupt catches, for precisely as long as I can keep my impatient mouth shut.

I can bring her only what I have, cut from the materials at hand, but I yearn to show her my best work. Somewhere among my possible realities exists the finest stuff that could possibly emerge from expanding the hollows of imagination, skittering along the event horizon one instant before supernova, at the point where everything there is flashes across a godlike awareness before exploding and collapsing to a shrunken stub of crushed and broken fibers, rotating listlessly along the axis of a galaxy that forgot us before we were born.

Before we became mortal in this brief, eternal instant.

I constantly envision what it might look like if tool marks didn’t crisscross my awareness like scars and tumors, like crimes and betrayals. Despite spending my whole life coming to this moment (as we spend entire lives coming to every moment; as the universe burns through galaxies faster than a fool breaks his tools), the patience of craft laughs at me, dancing one step out of reach while the last sand drains into the bottom of the hourglass, down.

Like water leaving mountains.

At the edge of the world, indigestible even to worms, a single grain of sand awaits. Its purpose is to show you the last visible increment of disintegration.

All my work remains a riot of contradictory patterns, catching me up and breaking down my edge. Every piece waves death like a stainless banner. Meanwhile I both pretend I’ve got all the universe’s time to burn like a nova, and also burn to finish strong, now, because every man Jack of us is constantly pulled inward by the black hole we were born around.

I work to thin that barrier just enough to open my mother’s view and my own, praying to shave out one last coil of understanding before we both burst through this moment, but I’ve lost my courage again. Even as I put up my scrapers and move to sandpaper, I’m haunted by tool marks. My walls are too thick.

I rushed it.

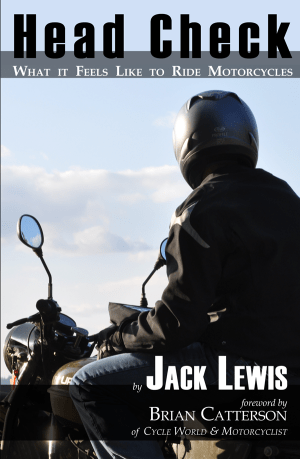

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

As usual, treasure assembled from paper and a pile of alphabet. Well spoken, Jack.

What is this “paper” of which you speak? 😉

A poignant reminder that we all have our knots and that shaping is up to us. How often we rush the process. Solid words that grip at heartwood.

Thank you, Lisa.

Probably should have sat on this longer and edited it a couple more times, but, well, y’know…

…I rushed it.

I read “Thinning”, twice, as is my wont with your writings (to double the enjoyment), and then re-read “Hallmark moment” which you wrote 10 years ago. Back then I told you that you wrote as well as William Gibson (my fav SciFi author). Well, I now must say that your writing is *better* than his, and in fact, *you* are now my favorite author (even though, as far as I know, you haven’t written any science fiction).

The breadth and depth of your personal lexicon astounds me!

I know your comments aren’t directed at humbling me, Marc, but that’s the effect they have.

And I appreciate it.

Thanks for rushing. I was beginning to feel a hankering for the grounding serenity that your graffiti brings. The fascinating mosaic of its multi-colored layers are like an epoxy that holds things together when when life gets thin. As does a hug from Mom or leaning deep into a familiar curve.

Well-said, HMarc.

Jack…thank you for sharing your observations, views, opinions. Always entertaining, always thought-provoking. And always worth a second read, if not more. The bowl is beautiful. Best to your mother.

Thank you, Tim.

I’ll probably keep up this graffiti until my last spray can runs dry.

Cheers,

Jack

P.S. I think Mom liked the bowl, if only because she received it pre-packed with Jordan almonds.

I’ve said this before and I will say it again; nobody writes like this. You are in a class of your own.

I’m going to buy a lathe and it’s your fault.

What I have left of faith amounts to this, Howard: every new tool, love, phrase, friendship, or destination expands our view of the possible. The things we work with, from piston ring compressors to mathematical theorems, become aspects of our vocabulary.

IOW, it ain’t the size of your lathe, but what you say with it… or what you sing.

I’m interested to see what comes off your bench.

I’m not buying a lathe. Closest I come to woodworking is my chainsaw; I do however have a beloved ageing large fragile dog, my brown eyed Diesel; I find myself already heartbroke at random times, watching her limp progress My great good fortune is riding, still. My balm. Cheers to ya Brother Jack, would that you keep writing please.

I plan to keep chipping away at it, Carl. And I plan to keep tucking Viki under her fuzzy blanket for as long as she can enjoy breakfast, treats, and ear scritches.

Jack, I will never look at my dads lathe the same again (which he used to repair furniture) or all the other antiquated tools in his shop. The lathe, was uncle Hughs originally, a true Scotsman and has many more hidden creations that sadly I will never know. You have inspired me to lay hold a turn or two on the antiquated contraption and perhaps gain a few more scares. As uncle Hugh would say if you going make a picture try to make a pretty one. I guess that’s what inspires existence. Thanks, D

Make something that no one else can make, and make it the best thing it can be from your hands and brain and heart, and you will never not have done that fine thing. Years after you’ve passed out of the living realm and no matter who owns it, it will still be yours.

We try to do the best we can with what we have. Some people have more of something that we don’t and we want it. We have something they don’t and they want it. Will I ever play guitar as well as SRV? Not a chance in hell. Could he ever have ridden a motorcycle like me? I doubt it. I’m guilty of punishing myself for not having other people’s gifts. I can’t stop myself. I just try to find mine and do what I can with them. Ya done good, Jack. You’ve done well…

BTW, if you want to make yourself crazy Check out a guy named Max Krimmel. I met him when he was first building guitars in Boulder back in the early to mid 70’s. He was experimenting with the most amazing finishes. Stunning guitars. Then he discovered turning. That’s all I’ll say. Check him out…

Thanks for the ref. I’ll give Mr. Krimmel a look. A bit of humility goes a long way… and I got a wallop of that from motorcycling. Ya know who can’t ride a motorcycle like me?

Me. =:D

But the lessons I took from 40-odd years of wrassling handlebars — and meeting people who were better than my dreams — were worth every bit of present restrictions.

My buddy makes coffee cups. I’d like to send you one. Very cool, last forever ceramic; unlike the coolest things I’ve ever “made”: airplane landings and IV starts [very similar, if you think about it]. When they are done, they are largely forgotten

I believe every act of grace, perfidy, cowardice or courage persists in some form, forever. This is as close as I come to faith.

In order to shame each other into decent behavior, we warn of evil living on down the generations, but that continuum logically must run in both directions: the good that people do lives on. This occurs whether or not it’s a fleeting moment of clarity, a home long crumbled to dust, a hopeful glance shared with your dog — or the time you pushed your sister down after she screeched at you, because we’re not always good, are we?

We have to live with ourselves, and others with us, and every intaglio that our willful, cellular collective inscribes onto the plate of the universe lives on in the memory of

…G-d?