I wrote this a couple of years ago, from entirely as dark a place as is implied by its title. Today, though I find myself broken and struggling in my body, and struggling yet more with the suffering of family and friends who deserve so much better, I often find myself repeating to my friends my own startled epiphany that I’m happier than I’ve ever been.

And also everything in here is as true as it ever was, as true as I could tell it, and will never again be untrue.

==================================================

She’s a brave one; I’ll give ‘er that. Durable and persistent, too.

When we dispensed with wary circling and and started to date, full disclosure required that I share my medical resumé. Back then, it included a surgical plate, shoulder injections, ocular lacerations, TBIs, and a dozen or so broken bones (my fracture count has approximately tripled since then; one shoulder is rebuilt; they scooped my guts clean with a spleen spoon and the titanium plate inventory now stands at five[1], but she wasn’t the agent of any of that). One of those fractures – a compound tibia fracture with separation, occurring precisely at the top of an already vintage Koflach ski boot, thence retired – put me into a full-leg cast over my thirteenth birthday, but what I didn’t show her mattered more than bumps and bruises.

We were three years into marriage before Shasta sussed out why I hate my birthday. She’s always loved her own birthday, the one day in the year when everything could be about her desires instead of everyone else’s needs. Those needs started early with her mother requiring protection, proceeding swiftly to her grandmother’s requirement for emotional abasement, and moving predictably forward to various partners’ requirements for nurture, scapegoating, and actualization. On Shasta’s birthday, uniquely among calendar dates, nobody asked her for anything – not care, not cooking, not validation, not even doing the dishes. It’s her day, and I want to honor that. G-d knows she does enough for me. Why would I take away her happiness? One day a year ain’t too much to ask.

Inconveniently, Shasta’s birthday falls three days after mine. Three days before mine, 27 years ago, my daughter died for no particular reason. Her post mortem diagnosis was Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, which is a scientific term describing doctors scratching their heads in confusion. Sometimes babies just… die. We need a name for it, and SIDS seems as good as any. The traditional term was “crib death,” which is arguably more descriptive and equally accurate, but the medical profession – like soldiering, marketing, and government service – loves its acronyms.

She knew about Flavia, in broad strokes, but not until we visited the tiny grave[2] did she put the dates together. “October 11, 1990-January 17, 1991.” Three months and nearly a week to put her mark on the world, and the kid nailed it – none of us, in any main stream or side eddy of two-plus extended families, can forget Flavia.

Of our twins, she’d been the strong one. We worried about her sister: gravely jaundiced, profoundly underweight, and bubbling with lung fluid. Flavia didn’t gurgle. She bawled like an angry longshoreman until we saw to her needs. She brandished her shock of red hair at us like a weapon of vengeance, made kissy faces with her voluptuous little lips, and regularly caved in the sides of feeding bottles with the burgeoning power of her hunger for life.

Then she was gone like smoke and I was all done with G-d, and birthdays, and trust. I took to wearing a black garter on my left sleeve from the seventeenth to the twentieth of each January. A couple of years later, I left the careful silence of our never-home apartment to spend my birthday alone, sleeping rough under a ’58 Willys in the company of my good dog Junior and a dented bourbon flask, deep in the snow-covered Bitterroots of Idaho. It seemed better, somehow, than spending it equally alone in the company of my inconsolable wife. I figured I could do moroseness just fine without an echo chamber. I am prone to pull my darkness to me and hitch it securely, close as a coal car firing the boiler of a Hell-bound express loco. Flavia’s mother did not leave the station with me. She always was wiser than that.

One night of winter bivvy having promptly reminded me of the worst parts of a peacetime army, I saddled up the following morning to wander downhill along the roads of least resistance, irrevocably restoring my status from ridgerunner to flatlander. At a roadhouse breakfast stop, I ran across a company of National Guardsmen, dressed for drill. They looked clean and dry; they looked purposeful, honest, and well-fed; they looked at me funny, and we all agreed to ignore each other. I called up a woman, drove that rattling ragtop to Spokane, washed out my whiskers, and spent the night.

The next day, I called up another woman in Pullman, showed up bedraggled on her doorstep, and followed her inside for hot, homemade ginger soup. By the time I made it back to Idaho, there was no marriage left to mourn. It was days before I realized, while packing a few clothes, guns, and some books, that my arm garter had blown clean out of the truck.

The woman from Spokane is dead now. During college, we’d lived together in a shabby, wood-heated farmhouse a few miles outside Palouse. We shared adventures over gallons of beer in traditional Coug style; Junior Dog was her puppy before he was my dog before he was, at his end, her dog again.

I think of her in January, because how could I not? I never see it coming. The dark time just forms over my personal event horizon, amorphous and despairing, a few days after Christmas. So far I always get through it, but rarely without damage.

One year I threw a sleeping bag and my dog (not the by-then-long-dead Junior, but my sweet buddy Tucker) into a crappy, reliable conversion van with electric blue velour upholstery, turned the key and didn’t say when I’d be back, or if. No promises were made except by Tucker, who prized steadfast loyalty above grief and displaced rage. I may have been smarter, but will never be as wise as was that powerful, fragile beast.

We got no more than a few miles from the house before he whipped his big Great Dane head around, white-eyed with distress. He yipped and growled, shook and whined. When he started gnawing a hole in my sleeve, I pulled over to phone my erstwhile home.

“Are you coming back?” Her voice was anxious, welcoming, forgiving; even tentatively warm.

“No,” I told her firmly. My voice gets radio announcer-grave when I’m deeply angry. “But the damn dog won’t leave me alone. He thinks I’m doin’ it wrong.”

“So you’re not gonna run away after all?”

“Of course I am, but Tucker’s in distress. Throw some stuff in a bag. If you’re ready in fifteen minutes, you and Jasper can come with me.

“Fifteen. Minutes. I won’t wait.”

“Oggie, too?”

I sighed. “Yes. Bring the Stench Hound.”

We spent that weekend van camping our way around the Olympic Peninsula, from inland lakes and trails to the Makah Reservation on Neah Bay, down through Moclips, and back home across the Narrows Bridge and north. The dogs tried chasing a bear and happily lost that race. My youngest daughter squealed at seals in the harbor, and my sweetie practically petted bald eagles. It’s a charmed memory, salvaged from dark winter wreckage and entirely irreproducible, at least by me.

Tucker died, not long after saving our family. His first cancer diagnosis left him three-legged, arthritic and stumbly, though he could still make pretty good speed in a straight line. A year later, his eye clouded over, killed out by another tumor, and I had to consider how much pruning he or I could take.

One Friday that January, I scheduled a house call from a kindly doc who deserved better work than contract killing. By the time the veterinarian showed up mid-Monday, Tucker’s lungs rattled from more tumor growth. He was shaking, listless, and non-responsive to anything but Swedish meatballs, which he nibbled at purely out of kindness to us. That day, after his great heart thumped out the last quiet beat of our friendship, I carried him barefoot into the back yard where he’d romped away much of his absurdly short life, goofing and flopping and randomly crashing into things. Occasionally, he’d lunged into my hip so hard it nearly crippled me, but lying inert in my arms is how my best friend gutted me.

Between his death and my 50th birthday, I beat a man for speeding through our neighborhood. Took a black eye, then kicked him around until it dawned on me that he’d lost his pants and I was out of breath, anyway. I guess it took my mind off things for a few minutes, but I take no pride in random rage. It loans you a brief, adrenalized distraction, then saddles you for life with a nasty vig.

January is also when I pause to consider the women. My scorecard is unenviable. Of those closest to me, one died ugly from cirrhosis of the liver. One went to prison for life. The mother of my children found herself abandoned in a quick divorce of surgical pain[3].

Three years after our divorce, my second ex-wife underwent chemo and a double radical mastectomy. I still have studio shots of her, consequent to having finally married a woman who understands that memories don’t threaten the present unless you hide them, like chemical waste, deep underground to foul your waters.

A girlfriend-turned-fiancée from grad school turned a good buck selling her Republican soul to K Street; if you find yourself annoyed by consequences of the Real ID Act, well… that’s her baby.

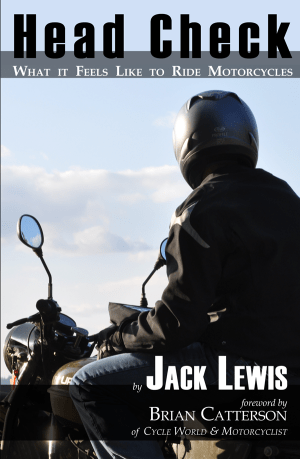

Now cometh Shasta – my forever wife in the manner of those who discuss “forever homes” for abandoned pets – who signed on for the full adventure, only to find out that motorcycling and the career we built together around that deliriously foolish, lifetime apprenticeship are receding in my mirrors, rather than dancing in the beam of my onward-pressing headlight. I don’t ride anymore, and I won’t. We still keep two bikes parked out front, and two more in the shed. Three of them are mine; only hers gets ridden. Dark days for black motorcycles.

And also to find that my murdering original fiancée is now released into the community, somewhere inside the state that we share. The security lights now ringing our house won’t shine into the hole she blew through my trust, nor ever brighten the graves of her parents. The South may not rise again but the past always does, shambling golem-slow out of the darkness of my mind to walk me down relentlessly while I scramble and slip like a wide-eyed starlet gyrating to the ominous, long-pipe tones of a theater organ.

I never meant to deceive her. Surely there were things that Shasta knew, but a literally homicidal ex- was one of the many more she could never have guessed.

Of course it had been January, sitting on my rack in a barracks during the late-stage global warming of a Cold War along the frozen Chosin, when I learned the details of my first love’s sentence. Her conviction resulted in two life sentences (plus 20 years!) for her but just the one, for me. A man of sorrows, acquainted with grief? No. Not really. Just a confused, overgrown kid, about to turn twenty. You’ve got to carry that weight a long time before you can be a man of anything.

During a different January, in a different country, on a different hitch, serving a different generation’s version of the same army, I helped evacuate a bleeding man from a private home in a war-torn city. Having flagged us down for transport, his father boarded with us and watched his son as he bled, unconscious of his lamentable hygiene, all over my boots while I kept my head up in the wind, standing in the air guard hatch of a Stryker and watching for more like him.

In case I needed to kill them, too.

It took eight years of learning to trust marriage before I admitted, out loud, that I killed that kid. Iraq’s historic elections – their first open balloting day in a generation – mark the month for me. There was a great deal of joy among Turkmen and Y’zidi citizens who were voting for the first time. I try to remember that, to tell myself it was worth it – even if we did cough up that region again, later, abandoning our erstwhile military protectorate to be rescued by the Kurds whom we would later abandon, as well.

Not a single one of those deaths, nor all of them in their grisly aggregate, justified any other killing. We imposed a brief political change, now gone like the smoke of a refinery fire, leaving just a poisonous stink of despair.

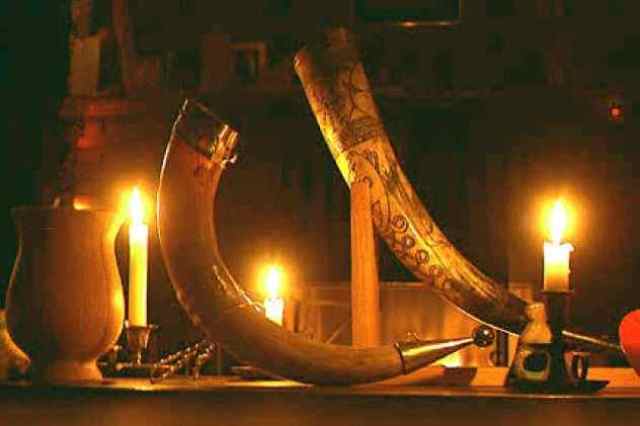

That boy, with his man’s weapon and his disconsolate father, with his beauty mark tattoo and his boy’s eyes, will have his Yahrzeit in our window this winter. He may have been my enemy then (is it okay that I pray he was?), but he’s nobody’s enemy now. All his potential for good or harm leaked away through a ragged portal that I opened in his liver. I see no reason to leave him out, no reason to pretend he doesn’t cast his own gloom into the shadows gathering near.

One by one, flicker by flicker, she finds each candle out. Living in my head is a process of continual re-discovery. Living next to it must be like living across the road from the Umatilla Chemical Depot – it looks peaceful most of the time, but down below are twenty million acre-feet of buried poison and you never know when the alarms will scream.

It might be easier just to map out the minefield of my heart to her; easy, if it weren’t impossible. Why do I grow a mustache in January? I don’t know – it makes me look less like a cop than a convict or a seventh-rate porn extra – but I’ve been doing it since I could barely grow visible whiskers. There must be some kind of reason. When I figure that out (or, more likely, she does), maybe I’ll be able to stop. Just like my iron-faced Grandpa Fax’s pencil-thin version, the damn thing is like brandishing a bladed weapon on my lip.

I do try to get my stuff together in time for my birthday. People close to me often go to great lengths to make it my “special day.” Because it seems churlish to blow them off, I grin along, pour drinks and turn on all the lights, pushing my shadows deep under the furniture.

Besides, it’s good practice. Shasta’s birthday calendars as close to mine as Flavia’s deathday, but on the other end. I need that three-day window during which to shed the Stygian pupal case that closes around me every year after our Chanukah mugs are stowed in the attic and the Christmas lights are de-mounted, re-tangled, and crammed into boxes. Like my people’s well-lit Jol, the Jewish festival of lights presages a new year of darkness, treatable only by the warmth of friends and family, and lighthearted banter interspersed with the occasional desperate, wordless hug. And survivable, maybe even for the long haul, by the grace of the bravest woman I’ve ever known.

Despite not knowing what lay beyond the false advertising of my cheerful swagger, she’s never once flinched from the things that scare me most.

[1] Giving me tangible salvage value. J

[2] It’s the same size as every grave in the cemetery, of course. When I see it, I always recall a white fiberglass coffin, nearly small enough to tuck under my arm, and the little frozen blue body that my first wife and I held, by turns, in the storage room of the Pullman mortuary. Perceptions are elastic over time. It’s a tiny grave, because it must be.

[3] A surgically painful procedure works like this: it takes place in a numbed state but hurts like hell during recovery. After scarring over, it continues to twinge at you for the rest of your life.

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Here’s hoping to contribute the light of a wee candle… I feel the hurt of the shadows. May you find in them the forge fires that turn pig iron into the finest steel ; stronger, more flexible without breaking, adaptable, beautiful. I wish you the power to find another fold every time you walk through the flame.

It hurts to know the path you have walked, but your experiences have made you the person that you are – – and *that* is a person I value highly. Very.

As I often say to people “I wouldn’t wish my experiences on anyone I *like*, or most folks I **don’t** like – – but they have made me who and what I am, and I’m okay with the current result”

Peace and Blessings, my Dear Friend

Love you back, Red.

You never fail to touch me with your words, sir.

Thank you for opening your.. what? Heart? Soul? Mind? Whatever that place is, I’m grateful you shine the light on it and share.

It’s just a mildewed closet full of jumbled night memories. Thank you for looking in there with me, Eddie.

It’s better to face monsters as a team.

Beloved friend,

Thank you for who are. Thank you for your energy when our paths cross. Thank you for so

Sharing so articulately your story and pain. I’m sending hugs and love and peace.

I know of no other person who is so capable, so vulnerable, and so open to sharing the details of their mental closet. You my beloved friend are an inspiration for the ages.

Thanks for sharing this. You do have a way with words! Not saying I enjoyed reading about your angst, just saying I enjoyed the way you wrote it!

May you be showered with good karma from your friends this year!!!

Thanks, Art. Hey, are you coming to PV this year? Fat Goose…?

Been too long between conversations for us.

It’s always heartwarming to see new words from you. I thoroughly enjoy the swagger of your prose and am repeatedly struck by your depth of character.

Thanks for the inspiration to improve my own.

I greatly admire your honesty and candor, knowing that by addressing the ghosts, there is a flickering hope that maybe this funk might not be so dark… Or last as long… Or hurt as much. One can hope. You do help the bell jar lift, if only a crack. Thank you.