I posted a tiny, white-hot rant on Facebook today, and it seemed to hit a nerve.

My little temper tantrum read like this:

“Sorry if this offends, but:

Those of you voting for candidates I respect, thank you. Full stop.

Those of you voting for candidates with whom I disagree (probably vociferously), you have my respect for thinking through your positions (even though you’re wrong) and voting your conscience and your mind (no matter how silly and unsupportable your rationale). Thank you, sincerely, for being a fellow citizen in the true sense of the word.

Those of you who won’t bother to vote because you don’t think it’s a good use of your time, or it won’t change anything, or the system is corrupt, or the issues apply to other people, et al: you’re the worst Americans out there. You. Not welfare cheats, or job exporters, or Wall Street banksters, or military protesters… you.

If you won’t even pick up a pen on behalf of your own country, you don’t deserve one.”

I got some thumbs up, some mild perplexity, and a little blowback.

Rather than debate political theories of enfranchisement on Facebook — certainly the moral equivalent of holding a civil engineering seminar over mud pies — I’m linking to this. Hopefully, this will go some way toward explaining my vehement opinion that voting is of life and death importance, and that holding back to “protest” choices you don’t think are optimal is the kind of First World problem that can vanish like the momentary, diaphanous smoke of a smokeless powder round. Please believe that your franchise — that ugly little pain in the ass, that cozening to a two-party system you never wanted, that… that unCOOLness — will make as precious a memory as your former athletic ability once it goes away.

I hope you enjoy this excerpt. Hell, I hope you run right out and buy Nothing In Reserve (don’t forget a copy for Mom).

But mostly, I want you to go vote, please. It’s the least you can do to enhance the common good.

Thank you.

==============================================================

GAME DAY

Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.

—H.L. Mencken, A Little Book in C Major

It’s a wonder I wasn’t shot in the head.

Two days before the election, I was sitting on top of a school in Tall ‘Afar, screaming at the top of my batteries. My manpack loudspeaker was shoved up against the wall at the edge of the roof. It repeatedly squawked out the eight pro-election messages I had pre-recorded on a borrowed MP3 player, plus a couple of messages Charger’s terp had recorded that morning to give credit to the passel of commandos who were officially securing the poll site. Charger Troop, 2-14 CAV Rattlesnake Squadron, with its several Strykers, three machine gun positions and attached infantry squad from Apache CO, was officially just backup.

I didn’t really see why I needed to be down there 24/7. There was no night-time mission for PSYOP to scream at civilians in the dark. But what the hell; whatever gets you out of the office, right? The annoying bit being that, since Russ was detached off to Task Force Tacoma and Will had inconveniently gotten himself shot, I had all the team equipment to hump around, solo.

C’est la guerre.

Previously, I had dropped off election banners to all the troops, plus No Parking and No Roll banners. Charger Troop managed to get one No-Roll banner up, next to a hospital entrance where drivers had no access anyway. No other banners were posted anywhere in town, and Charger Six didn’t want to give back his banners for me to post.

He wanted souvenirs.

Charger had recently gotten itself a new commanding officer. CPT Halsey, who had moved over from S4 when he got promoted, was doing OK as far as I could tell. Besides, it was hard to begrudge a few souvenirs to the guy who called me “the hardest working man on FOB Sykes.”

In retrospect, Halsey was probably better at PSYOP than I was. I was a better shot, though.

So I whiled away the desultory hours by blasting the nearest neighbors of that school with my impassioned Arabic plea to get out the vote. We didn’t care who they voted for. The victory, in this benighted, septic political backwater, was to vote at all. No one waved, stopped what they were doing, or in any way acknowledged the loony blaring appeals to democracy over their rooftops. The streets were empty except for three kids in their mum’s little house, across from the school entrance. She was a pretty thing, young and probably a widow. The kids would wave shyly, open up in a grin, then dart behind their mother’s skirts. I goofed around some, hot-miking clumsy Arabic greetings at the kids. Their young mother looked stolidly at the ground, but she didn’t pull her kids inside. Maybe she would vote.

Somebody had to.

“It’ll be a miracle if we get fifty people in here to vote,” I told anyone who would listen. The Iraqi commandos up on the roof with me grinned and nodded.

“Your mother and I had a high old time last night,” I added. They grinned and nodded some more. I wondered what they were saying about me.

“Stock-BELLI-coom!,” I screamed. That got them going. Means something along the lines of “go vote!” Well, I thought so, anyway. We all screamed it a few times, grinning like devils. Many thumbs were up.

Just like U.S. special ops guys, Iraqi commandos implicitly know they’re great looking and intelligent, many notches above their peers. They implored me to upgrade my messages, which referenced the Iraqi National Guard (since folded into the army); they wanted messages specifically telling the people of Tall ‘Afar that the election sites would be secured by the heroes called “commandos.” I found a commando lieutenant who spoke passable English, and we laid a couple of messages onto the DVR/MP3 that I’d borrowed from the Air Force JTAC who shared a bunker office with us.

The army didn’t give us the gear that we needed, but what army ever did? You go to war with the army you’ve got, soldiers are fungible but gear is expensive and G-D bless St. Rumsfeld, patron of richly endowed contractors.

The vanity did not end there. Every last commando had to get his picture taken. Pretty soon, my digital camera was toast, and I had one pair of batteries left for the election itself. So I just kept punching the button on my lifeless camera, gazing thoughtfully at the dead, black display, then giving them the thumbs up.

They loved it. They trust Americans: our friendliness, our sincerity, our faultless technology.

In case you’re wondering, the army didn’t issue the team a Nikon digital camera, either. My wife did. It had a lot of miles on it when it got back to her. Good thing we popped for the extended warranty.

Seems you can’t get one for marriages, though. Not even new batteries, come to that.

One thing that wasn’t about to go dead was the loudspeaker. I had packed an extra forty pounds or so of BA5590s, the army’s all-purpose radio battery that we also used for our speaker, into my ruck.

With 80 or more pounds of “manpack” over my body armor, two grenades, eleven full mags, GPS, knife, buddy aid kit, carabineers, and candy for the kiddies, I needed both hands and feet to tote my rig up the crude concrete stairs leading to the rooftop. Not to mention “Darth Helmet,” the five-pound coup de grace in discomfort that only Reservists and Guard guys wore by then. “Real” soldiers got the new, lighter, better suspended Modular Integrated Communications Helmets. The MICH was said to have several times the ballistic protection of our old school K-pots. But, ours not to bitch and cry, ours but to do and… never mind that part.

And so we squawked on, the commandos and I, trading lunches and punches and bilingual insults. I taught a couple of them what the safety on the AK47 was for, something that was curiously important to me. Those guys walked all over the place and pointed their weapons every which way. They all wanted to look through my optic, which was fine until one handsome bubba nearly dropped my rifle over the edge of the roof. That was the end of weapons familiarization. A fine time was had by all.

I knew damn well it was a complete waste of time. No one would come. A theater-wide boondoggle. But down in the lobby, they kept prepping tally boxes and stacking ballots, shaking up purple ink and going quietly, urgently down their checklists. And two rooftops over, Charger’s gunners were stacking ammo cans next to their machine gun position.

Election Day dawned overcast and cool. When I got up in the dark, in a side room that had been taken over by first squad, third PLT, Apache Company—grunts on loan to the cavalry—Tall ‘Afar was virtually silent. No cars had been allowed on the streets for three days, and there wasn’t a city sound to be heard that you’d recognize: only chickens, empty ghee cans rattling along ahead of the lonesome wind, and the sound of first prayer call wailing out, louder than my manpack and with centuries more staying power in the message.

On our third morning there, we rose up cold and stiff out of a smelly pile of bodies and scraped disposable razors over our stubble, picked through breakfast bars and Gatorade, stumbled out for a piss. Not a creature was stirring but a few grimy joes.

As the sun rose, so did the gunfire. Harassing fire from Ali Baba started early, and made us skip smartly along when crossing the parking area between the school and hospital. I joined a Stryker patrol on Charger Six’s vehicle.

We rolled through Tall ‘Afar’s nearby neighborhoods, not looking for a fight but finding several.

The commandos who were dismounted in the same area had a tendency to utilize what I called the “Reverse Polish Firing Squad” battle drill: they’d form into a circle, face out and blaze away in all directions. Our infantry—which didn’t practice it—called this 360-degree tactic the “Death Blossom.”

Iraqis with AKs were hell-for-brave, though. I lurked in the air guard hatch (convenient for ducking), securing the captain and scanning alleyways.

An Iraqi male poked his head out; I pointed my rifle at him and gestured. He poked his head out again and I buried a 5.56mm round in the front wall of his house about a foot over his head, ending his curiosity. This happened several times.

Usually with women, you only had to wave them in. Young guys were hardheads, though. It’s the same all over the world.

One hajji, about 200 meters down, kept looking around the corner, scanning, then withdrawing. A warning shot didn’t do it for this kid. A second warning shot chipped brick within two feet of his head. He looked again. The next time I saw him, he was trotting across the alleyway, toward the commandos’ position.

He was dressed in black. He was carrying something. It could have been an AK.

No pressure.

When the bullet smacked him, he went straight down. It was very non-theatrical. I wasn’t sure I’d hit him; it looked like he’d tripped.

I didn’t shoot again. Two people—not dressed in black, not carrying anything—ran out and dragged him back to where he’d started, at the corner.

I didn’t shoot them.

“What was that?!” The Stryker soldiers down below were hackled. Couldn’t really blame them.

“Warning shot.”

It came out calmly, this lie. I was a support soldier. A nice guy, there to help. I didn’t shoot people. I warned them, fair and square. It was a warning shot.

Then we got into gear, and rumbled off another block or two. CPT Halsey, busy on the radio, had never looked up from his maps.

We linked up with the troop XO a couple of blocks over. He was stopped outside a home, with more detainees and casualties than he could tote in his truck. We took on four detainees. They squatted on the floor nuts to butts, flex-cuffed to the front. Most times, we cuffed them behind their backs only if they were violent.

Charger 6’s terp eyed his countrymen like they might attack at any moment. Our Stryker instantly reeked of sweet cologne over well-developed human body spice, crossed with fear-pressed urine.

“There’s a civilian casualty in the house. Have you got a litter?,” asked the El-Tee.

There came a burst of AK fire from down the alley, and he yarded out his nine-mil to blast a few shots in the general direction, shooting gang banger-style with his hand tipped flat.

“Fuckers!,” he yelled, then holstered his weapon and grinned at me, waggling his eyebrows. Spirits were high. Ammo was free.

We had a litter. I broke it out. 1LT Bonney and I headed into the house, clearing it muzzle-first. Inside the house, a young man lay on the floor. He was wearing shorts and a t-shirt, without even the ubiquitous plastic sandals. This was January, and the temperature was probably in the mid-40s, Fahrenheit. I wondered where his clothes had gone.

He was a military-age male. I wondered if he’d been dressed in black that day.

The wound in his abdomen looked like maybe a liver shot. His eyes were glazed. We slung him onto the sled—he might have weighed 130 pounds, if he’d worn heavier clothes—and loaded him into the commander’s Stryker, tucking him onto the right-side crew seat. Crouching and looking around curiously, his father came aboard behind him and curled down onto the floor.

Full house.

A detainee had shit himself into his man dress, and the wounded man bled out onto the crew seat. Somebody prayed quietly in Arabic, another protested his innocence in broken English from his wobbly perch atop a bag filled with cheap Chinese rifles—including the one taken off him on a rooftop. A complete menagerie: like Noah’s ark, if it were launched from the Tower of Babel to sail through Hell.

The wounded man had three blue dots tattooed onto his ankle. I asked the commander’s big-eyed terp what it meant: was it a terrorist marking?

“No, for… for beauty.”

His wound was a clean shot, through and through. We dressed him quickly with simple gauze padding, and sped toward the hospital. I tried not to step on him as the Stryker lurched around corners and I banged my ribs off the sides of the air guard hatch, tiptoeing on the edge of the seat that held the wounded man while scanning for targets on rooftops and down alleyways.

We knocked a piece off a building corner with the fat-hipped slat armor and didn’t slow down. We had no medic along. A soldier down in the crew compartment held the edge of the litter up so my bleeder wouldn’t roll off onto the floor.

He was dead within minutes. The father’s expression didn’t change, though he never stopped looking at his son’s face. He was looking at eternity in that moment, and he couldn’t see us at all.

When we dropped ramp at the hospital, the terp helped me carry the dead man inside. Iraqi doctors slung him up onto an emergency table, right off the slag-strewn foyer. His father watched stoically while they performed thumping, violent chest compressions at the rate of about 90 per minute. It looked like they were trying to beat him back to life, to punish him for dying.

I wanted to teach them proper CPR. I wanted to yell at them to stop, leave him alone, quit beating on his scrawny, dead chest.

About the kid he killed in Mosul a few weeks earlier, our bachelor detachment commander had told Big Danny, “It was a good shooting.

“You’re in the clear.”

Big Danny, father of three, had replied, “You don’t fuckin’ get it, sir.”

Standing in the crunchy hallway of an underlit hospital, I looked at the father of the insurgent on the table and wished I didn’t get it, either. I wouldn’t know what to do with his forgiveness, but I’ll never know what to do without it.

CPT Halsey had warned me not to leave the litter behind.

“We’re running out of ‘em.”

So I asked for the green canvas litter back, and collected a couple more that had piled up in the hallways. The doctors stared hard at me as I carried out the litters. CPT Halsey’s terp backed carefully out under his oversized blue helmet, afraid to turn his back.

Gunfire was intensifying around the voting center by then. There had been a couple of significant explosions within a couple of clicks, which still sent up rich, black roils of smoke. I gave CPT Halsey back his litters, and picked up my speaker pack. For about 20 minutes, as Charger troopers blasted concrete fragments off a beautifully finished luxury home across the MSR and the AK fire skipped around us, I broadcast my pro-election spiel over a masonry wall near the school.

The voters trickled in.

They walked, most of them, with the dignity of righteous action. One voter was shot in the belly. By his own insistence, he was carried into the polling place to vote before being carried across the lot under fire to the hospital. I guess they let him jump the line.

Some ran, ducking and holding their headpieces but coming anyway. Coming to vote.

I took a break from broadcasting to run a few boxes of 7.62mm linked-belt ammo for the machine gunners, who were having way too good a time, then got back on my squawk box.

The squadron commander rolled up in his personal, hotrod Stryker. He was waving at me. I waved back. He waved harder. Friendly fella.

1LT Bonney trotted over, ducking the fire.

“Rattlesnake Six says shut that thing off!”

“What?!” I had plugs stuffed into my ringing ears.

“TURN IT OFF! Colonel Pingel says you’re just pissing ‘em off!”

“The fuck does he know?”

“Just turn it off!”

“Roger, sir.”

Guess I didn’t convince him: negative impact indicator for that PSYOP mission. Back to the unemployment line.

A lot of good men thought that LTC Pingel was an egotistical, hardheaded idiot, a nepotism beneficiary who couldn’t find his ass with both hands and a flashlight on a clear day and who cared about nothing more than grubbing for his star, but how would I know about that?

I was just a staff sergeant. I shut it down.

Since I now officially had nothing left to do, I rejoined my adopted infantry squad to patrol the nearby streets on foot, looking for shooters who were targeting voters. I took along my digital camera. We waved and smiled at the voters, then crossed the MSR over to where we’d been receiving fire from. I put my camera away and brought my rifle to low ready.

Just a straphanger, I tagged along and pulled rear security for them. I hated walking backward, but as an old broody hen who should have been home with my own kid, it seemed like the place for me.

We got nothin’.

Policed up some AK brass from an intersection, tactically questioned a couple of guys, and neutralized no one. We did figure out that the gunfire was coming down the alley on an angle, and that Charger’s two-forty gunners were shooting at hallucinations, but that wasn’t a huge surprise. They were just having a good ol’ time up there, rocking the gun. Every time a round or two came down, they’d cheerfully burn through a belt and a half in response.

We spent a lot of your money that day.

Our little patrol shut down the constant AK fire, though. The rest of the city was a hodge-podge of scattered gunfire and the occasional big, black, smoky boom, but the consistent fire from across the way was stopped. After that, it was just sporadic, hit and run stuff. One Stryker gunner had the charging handle of his .50-cal. shot off in front of his face, but he was lucky. No Purple Heart for him that day. Eye pro rules!

And the voters rolled in.

They came from all over the city. They came with their children and donkeys and wives. I look at the pictures now and can still hardly believe the lines. Thousands of Iraqis, holding up their proud, purple fingers. Women, bandaged head to foot in their burkas, voting for the first time in their lives. Venerable old men voting in maybe their second real election. Young, hip guys in sharp Western suits. Farmers in grubby dish-dashas. Donkey carts and favorite dogs. My favorite shot was of an old man, his young son and his old wife, all giving me the finger in lurid, living purple.

It was a sight to see.

It went on and on. Twelve thousand people voted in Tall ‘Afar that day, and each of them had to risk their life to do it. People in my precinct wouldn’t go to vote if there was heavy traffic.

I hadn’t voted in person in years. That was what absentee ballots were for, right? Right then and there, I resolved to go the following year, if only to shake the palsied hand of the old bat manning the booth. She had suddenly become one of my heroes.

I would fly home to a state that gave up setting out polling stations. Too inconvenient. Too expensive. Nobody cared.

By 0200, we had policed up hundreds of spools of concertina wire and thrown them onto enormous tractor-trailers. The trucks were packed up, fueled, ready to go. The ballot boxes—precious cargo—were sealed and loaded, held under guard. I sat in the Charger commander’s Stryker again, too bone-tired to move. The radio squawked, but I ignored it until CPT Halsey sighed.

“It’s going to be awhile longer.”

“What’s up, sir?”

“We have to wait and secure the HETS. Should be about forty more minutes.”

“You know, we really did something here today, sir.”

I rolled my head around to the sound of crackling neck bones.

“At least, I think we did.”

“Yeah. Let’s hope they can take it from here. This country needs to carry its own water next time.”

I lit up a smoke, unauthorized in military vehicles, and sucked on it until my eyes itched too much to want to close. The captain looked at me.

“It was something, though, wasn’t it?”

“A sight to see, sir.”

And so we waited there, wakeful but bleary, until we headed back to the FOB around 0530 and made it to the DFAC before it closed at 0800. That had to be the best KBR chow I ever ate.

I’d been up for thirty-some hours by the time I got back to my hooch. It didn’t feel historical, not then. Like most of the joes, most of the time, I was just tired.

My knees burned. My back ached. My eyeballs itched with harsh corneal fur. I cared only about ripping the batteries out of the manpack, filing my report and staggering off to the rack. That night, I ran another mission with another unit—a cordon and search, probably—and the night after that, and the night after that, with daytime Battle Update Briefings in between.

I didn’t think about Election Day again until much later.

I’m really not sure what I think of it now. Of my experiences in Iraq, this was the hardest to parse. It wasn’t the best of days or the worst of days. There were elements of both. In some ways it was a high point, a kind of crisis in the harem-scarem plotline of that scattershot war.

Or peacekeeping operation. Or counter-insurgency. Whatever we call it these days when we task our Department of Defense to kill folks overseas as a policy statement. It’s an active sort of defense.

In other ways, it was just another day at the office. I formed no tidy thoughts about what my teammate called “Game Day,” except maybe for this one: the good guys didn’t win, and the bad guys didn’t win.

At least that one time, the home team won.

Game Day appears in Nothing in Reserve: True Stories, not War Stories, which is available from publisher Litsam.com, and also in many bookstores and on Amazon.com.

Game Day appears in Nothing in Reserve: True Stories, not War Stories, which is available from publisher Litsam.com, and also in many bookstores and on Amazon.com.

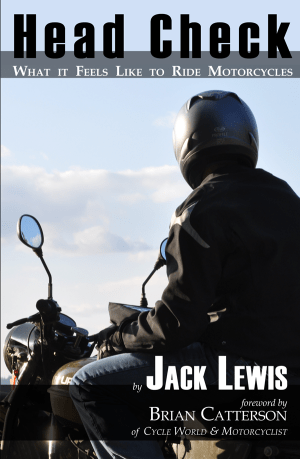

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

As always, Jack, you are the best. And I voted today in Missouri.