With the rain slowed to a drizzle, we sat around a guttering fire, working cuss words into the conversation for practice. Intent on winning this little competition, I was the last to notice that the other guys had shut up. And looked up.

“Can I help you, sir?,” said the kid across the fire. That was Dey, blue-eyed and dark-haired, about my height and quiet. He’s a teacher now, I think.

Jones, a lanky redhead two years older and socially retarded enough to revel in his falsetto tagline of “Go to bed!,” sat next to Dey. He sniggered up his damp, snot-armored sleeve.

That morning my friend Billy and I had pitched all of Jones’s gear out of our tent and into the rain, following a wrestling match with the much bigger kid over who would sleep in the wet spot at the center. It took both of us to put him down and grind his freckles into the mud. While I explained things to our unimpressed scoutmaster, Billy eased around the far side of the tent and meticulously pissed in Jones’s canteen. And Sierra cup. And beret.

We’d been parlaying over these events in colorful terms, thumping our scrawny chests in prelude to further Alpha Shrimp shakeouts, when the cone of silence descended abruptly. I hesitated a moment before looking behind me.

Blocking out the sun was a huge man wearing a brown pinstriped suit over square-toed engineer boots. His right lapel bore an enameled American flag pin; the left, over his heart and wallet, the blue flame logo of his company, Western Propane.

“Uh, hi… Dad—.” Pinching off the word before it could stretch into “Dad-dy” made me stammer like an early-adopter drunk. He was smiling, a little. I couldn’t guess why. I didn’t know how long he’d been standing there. It wasn’t his weekend, but his offices were nearby the Delta Park tenting ground of Encampment ’76.

Dad waited for a minute for me to figure out that I should stand up. Realizing that I wasn’t about to hug him in front of the guys, he put a hand on my shoulder. My baby blue down jacket – wheedled out of Mom at a Fred Meyer sale in that year of down jacket and waffle stomper requirements – had degenerated into a moldy clot, streaked with yellow mud from our earlier festivities and bloody brown around the knitted cuffs. My nose bled at the drop of a hat, especially if said hat happened to be a piss-weighted beret ground into the mud.

“You’re a little wet.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Can you take a minute?”

I reckoned that I could. Escorting him across the jamboree ground, I babbled on about its wonders to prove that I’d been getting involved: hatchet throwing, patch trading, hot chow lines. Respecting my body language, he didn’t put his arm around me despite the wracking shivers I’d been fighting for a day and a half. I had missed that camp fire since the moment I stood and turned away from it but the softer a boy is, the harder he talks.

We climbed into Dad’s big, brown Merc, a dual-fuel Cougar with manifolded propane tanks in the trunk. He cranked up its 400 v8 and the excellent heater without a word, then drove me to G.I. Joe’s where for four bucks we procured dry long underwear and for two more a green rubber, duck-billed, army surplus rain parka, five sizes too big. For years I harbored that crunchy, smelly rag, imagining I’d never have another chance at such a vintage bargain, until the army issued me one just like it for the low, low price of four years’ indenture.

A couple years later, after I figured out parallel skiing and shot the bowls for ten hours just to prove it and crashed badly on the last run of the day, stumping back to the already-closed ski patrol shack on my busted tibia, it was Dad who showed up to drive me down the hill to Gresham Hospital.

All the way there he insisted that it couldn’t be broken, but I could feel it crack and grind when I moved it so I mostly sat across the back seat, white-lipped and trying not to move. Or complain, because it was my fault. I was the one who had broken a Lewis.

Three years later, when I broke the other shank in five places at once, Dad came blazing out of the cocktail party he was throwing. Broadsliding Grandma’s ’68 Lincoln up the same dirt road down which I’d just thrown my dirt bike, he eased me in through the suicide doors and drove across the highway to Dr. Shenkar’s house to pry him out of his own cocktail party before driving me on to St. Peter’s hospital.

Ambulances are for civilians who don’t take care of their own.

A couple years on, it was my stepdad who drove up Chehalem Mountain to pull a logging chain out of his Travelall and slowly ease Mom’s Country Squire LTD out of the ditch into which I’d slammed it the night before, subsequently hitching a ride back down to the valley in a ’68 Mustang driven by a guy as foggy-eyed as I was.

Not long before, Paul had shown me how to use a come-along to pop out the nose of the Volvo wagon that I’d punched in like a bulldog’s snoot by rear-ending a beater Dodge Challenger. A few months later, my stepdad, who really deserved better, recovered that same Travelall from someone’s lawn where I’d managed to get stuck up to the axles while turning around in… wet grass.

Because Triple-A is cheating.

In basic training, it was Drill Sergeant Tajalle who ungently explained to me that he wouldn’t give up on my pansy ass just because I kept puking on platoon runs. Neither, I was given to understand, would I. Then he smoked me until I puked. Again. And again, and again, and again until I could run mile after mile in boots and gear, body a machine lashed into Uncle Sam’s service; mind clear and empty and fearless, an uncarved block of soldiering potential.

And a hundred other rescues, large and small, consistently accompanied by genteel overlooking of my sore-thumb culpabilities.

Next to the originals, second-generation xerographs look a little faded, but I try to hold up my end of the board. My daughter, more self-reliant as an entering freshman than I was as an ammo sergeant, has made minimal recourse to the Daddy salvation network over the years. With me squandering most of those years wrapped into Vitally Important corporate drivel or deployed alongside other people’s kids, she learned self-reliance early.

Mostly now I pass along tools, which are actively useful, and advice that is accepted in gracious spirit – even when it’s not my weekend. Grown now, all her weekends are belong to her. If we’re lucky, she’ll need some baby sitting one day.

At least my stepchildren are kind enough to forget their lunches occasionally. Saddling up to drive 30 blocks to the high school may not constitute an Emergency Deployment Readiness Exercise, but it gets me out of the house. It keeps my juices flowing. It gives me a chance to paw through my attic, find the bright souvenirs left by bigger and better men, and carefully rub a little Brasso over them.

Thank you, fathers. Thanks for putting up with me. Thank you for saving me, all those times, mostly from myself.

Happy Father’s Day to you all.

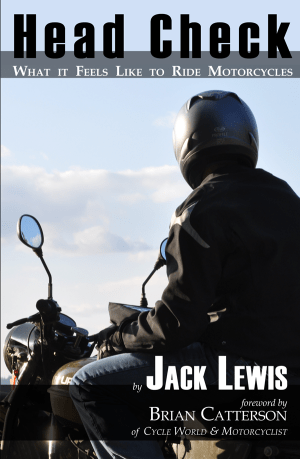

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Going to send this to my own dear da, who only had to carry me from the field of juvenile battle the once… when I was but three.

Nice of them to come along when you need picking up, whether from the ground or the police station. It was understood that there was only one get out of jail free card to play, and the grounding and work in the yard for a month was the only free thing. He is gone now, but still was picking me up, at least mentally from my injuries until the day he left. Parents are great for picking you up, whether physically, mentally, or both. Thanks for the reminder Jack, your old man did a great job!

I sheared off a light post learning how to drive drunk at 21. Dad found me in ER with a broken nose about to confess my sins to the waiting cop. He walk in, told me to shut up and told the cop he would have to wait until the Doc arrived before the could draw the blood for the DUI test. I had quit drinking at 11 PM, hit the pole at 2 AM and was legally sober at 4 AM when they finally drew the blood test. Thanks Dad!

PS … Dad was also responsible for my motorcycle addiction.

If it’s true that our species is alone in the universe, then I’d have to say the universe aimed rather low and settled for very little

When you order frogs legs at a restaurant what do they do with the rest of the frog ? – Well surely they just throw the rest of the frog away and take it to the tip.

Sent via Blackberry