Born in 1893, she was the eldest. Eldest sons assumed their family’s fortunes — however plush or mean they may be — but an eldest daughter assumed only responsibility, even if she grew up in a town bearing her surname on its sign. She left school after the eighth grade, discarding academic promise in favor of helping to raise her siblings.

There were eight of those, brothers of promise and sisters, too. Women hoed a hard row then, in California as everywhere else. Her mother needed the help, and she was obedient. She played for the home squad. She did her duty.

The day her youngest sibling entered high school, she transferred to the traveling squad. There was some money, saved from working outside the house. She’d skimmed her paycheck slightly for years, money from dairy milking, from piece work stitching, from waitressing and baking and growing produce. It was considered family money but she was family, too.

It was her turn.

She took her savings to the train station, packed into a cardboard suitcase alongside two changes of clothes sewn from disassembled hand-me-ups and dismembered house linens. Of all the family’s children, she was the only one who never reached five feet in height. Genetics? Nutrition? She stood solidly on size 10 feet, in boots that were made for walking. For traveling. Maybe even to fly.

Her boyfriend — despite a campaign measured in months, he never reached the status of “beau” — roared up to the rail station as she was pulling open the door, but timeliness wasn’t everything. It was his Harley-Davidson Model J that made her blush, not his advances, and her mind was made up. She marched to the ticket window, laid out her money, and asked how far she could go. So early in that fresh American century, the clerk’s answer was instructive.

“As far as you want to, Miss.”

She debarked the train in Washington, D.C., worlds away from the bucolic coast where she’d grown up in the saddle of a tiny, castoff, painted pony. She took a room. She took a job. She took a look around, and saw nothing for her in that town that was dirty with mud streets, swamp skeeters and political intrigue.

Nothing but possibilities.

Without a high school certificate, she bluffed her way into nursing school based on charm, persistence and native brains. If Abraham Lincoln could study law by candlelight in an Illinois cabin, she’d reasoned as her siblings grew and made their way in the world, there wasn’t any reason she couldn’t read up on medicine while she rocked a cradle, built up a cook fire, fried eggs and sent her little brothers and sisters off to a privilege she had lost.

Was she properly prepared for nursing school? No, but she was readier than anyone. She kicked a hole in her classes. She kicked in saloon doors with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Trading in her riding scuffs for soccer boots, she learned to kick a ball around and joined a women’s league soccer team… in 1917. Just family lore? Sure, but there’s a picture. Here’s the lore part: despite being the smallest woman in the shot, she became the team’s leading scorer.

She also became her class’s graduation speaker, a soup kitchen volunteer, a member in sober standing of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

And a registered nurse, of course.

The next photograph I know of was shot on Figueroa Street in Los Angeles. No more boots now, she’s pictured linking arms with a tall man in a coat, tie and silverbelly Stetson homburg. Their smiles (and feet) are huge. Hers are in a pair of high-heeled pumps that make her just barely five feet tall. He is six foot-three, even without the hat, a big handsome former U.S. Mail pilot and jazz drummer helping to build the mythology of the City of Cars (and, just incidentally, Angels) with Model A Fords driven over from the oil fields of Texas to sell on a used car lot where one day his sons would wash them up for a nickel per jalopy.

They moved out to Monterey Park and founded a hog ranch. He still sold cars and she still nursed in L.A., but now they also had three sons, one daughter and a thousand piglets to raise. It wasn’t enough to keep her from making missions to Mexico. If you were a man in the church, you could aspire to elderhood. Women could be missionaries, and her Spanish became excellent; her children, bilingual.

In the 1940s, they sold out of hogs and moved to the eastern Oregon cow town of Baker, where my dad grew up believing in cowboys enough to call himself one. That didn’t sit well with a home-grown kid on the bus, who knocked his little cowboy hat off and precipitated a fistfight that lasted 42 minutes until one of them finally had to get off the bus. After that — and on the bus driver’s strong recommendation — he walked to school every day, running home afterward where he might find his mother, ever the nurse, salving and bandaging their freshly branded cattle.

Well before he was anyone’s dad, Jack Lewis, Sr. learned to hunt and fish from his own tall father. His mother taught him hygiene, manners, driving, economics, and a level of enterprise that would propel him to found corporations and endow university buildings. She also taught him perseverance, including the object lesson implicit in her having shot a grouse at close range with a .410 handgun. Thinking more about dinner than technique, she drew the gun up to her eye as though she was sighting a rifle. The kick split her eyebrow in a way that would be hard for her husband to explain for several weeks. After staunching her own bleeding, she nonchalantly field dressed the bird and tossed it into the trunk to take home for their supper.

Every year they took a summer trip — first in Fords, then later in a series of Mercurys — to Yellowstone National Park. Along the way, they’d eat berries, hunt small game, and indulge in the occasional roadkill if it were fresh. My people may be proud, but we’re practical.

The middle son, an uncle I’ll never meet, died of spinal meningitis when he was eight years old. Not every dorsal problem can be nursed away, but strong backs do run in the family. Her youngest son fractured his spine before that first, fateful school bus ride. She put him to bed, fed him chicken soup, then clapped him into a mail order truss when he became too energetic to keep down. Once a nurse, always a nurse.

He was taller than she was by the fifth grade, but still too short in high school to play for the basketball squad. So he got his own group together. Calling themselves the Alley Cats, they handily beat the varsity team using the same brand of speed and agility that worked so well for women’s soccer on the east coast. Once her own children — the second generation she’d launched — were raised and fledged, she and her tall husband sold the ranch and moved out to Idaho, where they bought the first 4WD truck in McCall (a 1951 Willys), hunted from horseback, and bought a travel trailer. She still had a yen for Mexico. They went many times.

On one of those trips, someone came tapping a club along the side of their trailer while they parked on the shoulder for a rest. With her husband asleep, she poked an Iver Johnson six-shooter through the window and waved it at the curious party until he departed. That time, she remembered to keep her arm straight, just in case. Plastic surgery wasn’t in the budget, and she already bore a bare spot through her eyebrow in the shape of a grouse’s wing. No need to spoil a perfectly good vacation.

By the time I knew her, they had moved back to Oregon, where she kept a tidy house at the end of a bent dirt road. In the driveway were parked a tiny, red and white, fiberglass fishing boat; an enormous ’69 Lincoln Continental with electric blue leather; and a black, 1965 Mustang fastback with a V-8 engine, “ponies” interior and a four-speed transmission. It always had two Portland telephone books on the driver’s seat, to push her far enough forward to work the pedals. Her boots were made for driving.

I was always a little afraid of my big, gruff grandfather, who still wore a silverbelly hat (no longer the cosmopolitan homburg, he had shifted his preference to a “cattleman’s crease” Open Road, the style favored by hated Democrat LBJ; still a Stetson, of course) over scratchy Pendleton shirts in the winter, and lurid Hawaiian shirts in the summer. Even when he was inviting his grandkids up onto his lap, he boomed like big sky thunder.

Still, he was a reliably gentle man and a gentleman to the last, perhaps secretly in a bit of thrall to his determined, tiny wife. After all, he’d never entered a saloon with anything more threatening than a pair of drumsticks. When she had gone to the bars in her younger years, she’d packed a sheaf of self-improvement pamphlets.

And of course (“For God and Home and Native Land”) an axe.

She grew every kind of garden crop, and foraged widely. Because of her, I know and gather boysenberries and salmonberries and black caps and thimbles, but I’ve never had her mycological nerve. At a central Oregon lakeside cabin, she taught us to trap crayfish, catch rainbow trout, and eat like the kings of freedom. We caught crabs, hunted ducks, and ate garden greens as much because Grandma said it was right and godly as because it was, well… cheap. At a beach near Lincoln City, she said nothing as a bystander sneered at “that crackpot old woman” scraping indigo mussels off the legs of a pier.

I still wonder what that jackass pays for gourmet mussels in restaurants today. I’m sure he never guessed that she and her still tall and dashing husband flew a Piper Comanche to Mexico for vacation every year. Her job as copilot was to remind Grandpa to retract and extend his landing gear, one of the several refinements (including closed cabins) that hadn’t existed on the Curtiss biplanes he flew up and down the West Coast in the 1920s, navigating with dead reckoning by day and flying between bonfires at night.

She still had that big, creamy white Lincoln by the time I was driving age, complete with factory option “AM/FM Signal-Seeking Radio with Dual Rear Speakers and Power Antenna” ($244). She was chief pilot by then; the same telephone books from her old Mustang now lived on the Lincoln driver’s seat, worn smooth by 16 highway hauls to Mexico. Grandpa had been bigger, but no one was more durable than she.

To avoid more scratches down the suicide doors, I’d been pulling her car in and out of the tiny garage at her retirement house and waxing the beast for her, hating everything about it until the day she let me drive it. The most aggressive thing she ever said to me about that was, “Now, don’t be obstreperous, Jack.”

At the time, she was attempting to dissuade me from speed-testing her car in fairly heavy traffic. It was perennially okay by her to set a good, tall cruise speed on less trafficked roads, though. She was four feet, eight inches of the gentlest kind of fury, and she stayed that way for another thick package of years.

Long enough to rehabilitate from a four-wheeler accident when she was 88 years old. Long enough to swim thousands more laps, grow hundreds of pounds more vegetables, and live to be 101. Not long enough to get Jesus into my heart, but long enough to change my life on her own merits.

Standing over her last bed, I was blessed to hold her hand and sing every hymn that the African-American R.N. and I knew in common. I don’t know whether anyone was saved, nor do I care, so long as Grams felt safe and cared for at that moment. She was 101 years old, and that was the first withdrawal she ever made from a care account into which she’d been contributing since before she ever cracked a nursing textbook.

Her Mustang was long gone by the time she passed, but I had one last chance to drive that big old Lincoln. Looking out across its half-acre hood and listening to that glorious, high-compression engine wind up as the strip speedometer spun out to the right like some hyperanimated barber pole, I could almost hear my Grams gently admonishing Grandpa, each time their speed dropped below 90 mph en route to Baja California, “Keep it up to speed, Charles. Keep it up to speed.

“We still have a long way to go.”

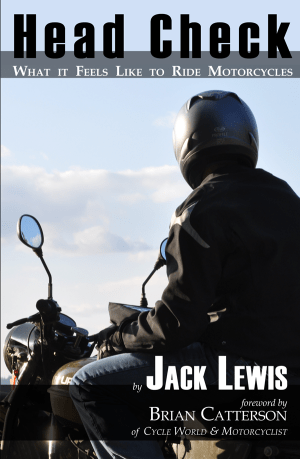

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Thanks, Jack………….makes me think I should put some of my families stories on paper (or computer or whatever) Thanks for sharing.

You are ‘Finest Kind’. With progenitors like these it’s no surprise to me.

Shalom!

This is a great read, a story well worth hearing told well.

Thanks!

Damn blurry monitor…