Packing my Ruck

I am just a poor boy, though my story’s seldom told I have squandered my resistance For a pocket full of mumbles, such are promises All lies and jest, still a man hears what he wants to hear And disregards the rest.–Paul Simon, The Boxer

1964-1982

My dad could do anything; this was an observable fact. Dad founded and built companies on weekdays, fixed the furnace, painted our antique drafty house, and restored rickety old Fords—the kind called “Model (pick a letter)”—in his non-existent spare time.

One weekend a month, Dad would disappear before dawn on Saturday and reappear Sunday in time for late supper. He was out flying, which had to be the coolest thing in the world. When he flew his lumbering Albatross amphibian over the house we would wave furiously, scampering around our yard like ants drenched in gasoline.

When Dad returned home from drills, or from two weeks of survival training and salmon fishing in Alaska, he would stride up the walk dressed in an orange Air Sea Rescue jumpsuit spangled with wings and badges and patches bespeaking competence and courage. Smelling faintly of beer and White Owl cigars, he completely filled the estate-sized door frame of our rambling, big old house. He was the biggest man in the world.

I still have a boxful of those vividly embroidered totems: blue-backed unit shields, shiny black name plates, and frosty command pilot wings. The air force wears a lot of such things. His earlier units had borne crests bedecked with swords and attacking buzzards, and I know Dad missed the glamour of the fighter jock he’d been while wooing Mom, but my favorite emblem has always been the Reserve patch from his search and rescue days with its proud motto: “That Others May Live.”

How do you top that raison d’etre?

My parents split the sheets when I was five years old. My big sister settled into hating my father with a grudge she would hide like a private Easter egg for the next thirty years. My little brother ran down the front walk, hugged Daddy’s leg crying, and begged him not to leave. I worried about my red-headed baby sister—she was too little to understand why humans pick at their own, self-inflicted scars until the pink seams split and the blood flows.

Maybe we were all too little, Mom and Dad included.

That night at supper, I picked up my plate, moved to the head of the table and gravely told my mother I would take care of things now, because I was the man. She was too kind to laugh and too strong to cry, and I tried hard not to look scared, and we agreed between ourselves that Grandpa could sit in that chair when he and Grandma were over for dinner.

After their divorce, my parents agreed on very little, but they did see eye to eye on the general virtue of preparedness.

On visitation weekends, Dad would push us to hunt, fly, drive, and operate gear ranging from go-karts and snowmobiles to chainsaws and Roto-Tillers. By the time I was thirteen, I could dock a twin-screw boat and shoot nickel groups at 100 yards with a thirty ought-six. A lurid scar from flipping a three-wheeled Honda “all-terrain cycle” striped my left thigh. My wallet held a SCUBA certification and my first traffic ticket, achieved while blasting a two-stroke motorcycle down Cooper Point Road to freshman football two-a-days.

The juvenile court judge, worried that I was veering hard left into sinister territory, clapped me into diversion counseling. But I think Dad was secretly pleased. He punished me by yanking me out of school for a four-day weekend of hunting around Othello, an Eastern Washington town where we wing-shot enough pheasants, ducks and geese (and one lonely chukar) to feed a family of six until they passed feathers.

Dad told us stories about fighting and never giving up, about how smart people were only effective if they worked hard, too. He fought his insurance company to and through the Oregon Supreme Court over coverage for a sunken Chris Craft, and brawled with his lead para-rescue jumper across two parking lots and a public street just to establish who was the lead dog. Dad consistently admonished us to take care of ourselves, because it was certain no one else would.

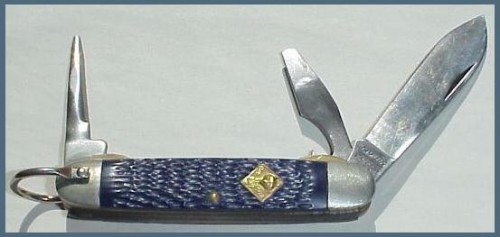

Mom’s more programmatic agenda for preparedness involved a lot less gear, and a lot more agencies. We were enrolled into Cub Scouts and Webelos and Boy Scouts; in Red Cross swimming, in church choir and violin lessons, in shop and Home Ec classes; in Little League baseball, Pop Warner football, Golden Ball basketball, karate and soccer and tennis at Hillside Community Center, and ice skating at the Lloyd Center mall. I escaped NASTAR ski racing only by the somewhat pathetic virtue of double-fracturing my right tibia and limp-hopping back to Multorpor Mountain ski lodge with it—following that ill-advised move, I dragged around a full leg cast for nine weeks, and was exempted from the slalom thereby. She may have worried about tree climbing, but Mom still insisted we learn knot tying, basic first aid and boot maintenance.

Sometime between my folks’ divorce and junior high, I made a choice to accept endurance as the price of my life. This switch-flipping epiphany was a sort of junior-level gestalt, like suddenly learning to whistle through my teeth, or to ride a bike with no hands—a pre-cortical thing I didn’t know how to do, but still somehow could do.

If I would be stuck with being a clumsy kid combining the athletic potential of a sea cucumber with the scintillating social presence of a picnic table, at least I could be the boy who wouldn’t give up, who always took another step. My heroes weren’t baseball stars. They were draft animals: Eeyore, the resigned donkey of Pooh Corner and Boxer, the doomed community pillar of Animal Farm. My work would never be fun, but would always get done—that was my sad, blighted little promise to the world.

Strictly due to Mom’s insistence (since I would rather have sat on my can and read a book), by the age of ten I could administer CPR to drowning dummies rescued from Couch Pool, properly sharpen a double-bitted axe and nail the descant line of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, pitch-perfect—a talent that would evaporate the year my voice changed. She also led dozens of stealthy missions whereon we rescued chipmunks, dogs, bats, doves, scuffed and drunken vagrants, and a plethora of parasite-ridden kitties from their otherwise inevitable and untimely fates.

From Boy’s Life magazine and my Scout Manual at home, I learned that you could stumble across disaster—a lightning strike, heart attack victim or auto wreck—at any time. The Scouts’ motto is “Be Prepared,” and woe betide the lazy boy who hadn’t studied ahead and practiced to save the day that needed saving. Ergo, I had my first exposures to CPR, pressure bandages and even tourniquet application long before the army taught those lessons (alongside such other common tasks as weapons maintenance and the proper deployment of Claymore mines).

Dad’s American Rifleman magazines had a slightly sharper focus than Boy’s Life. They explicitly pointed out, in between loving profiles of gold-filigreed L.C. Smith double-bores, that occasionally bad people would show up and need to be shot. Eventually, various drill sergeants would reinforce the point. And then insurgents would show up and prove it, but that was too far in the future for a nearsighted Boy Scout to make out.

Mom’s stories were qualitatively different than Dad’s. She spoke about nurturing bantam chickens, shopping with Cambodian refugees, and making our school’s PTA a force to be reckoned with. In her patched jeans and old wool sweaters, Mom personified substance over style and was never happier than when she realized she could wear the Adidas Stan Smiths I outgrew in the seventh grade. Her consistent message was to take care of people who couldn’t take care of themselves, because it was unlikely anyone else would.

Fully subscribing to both my parents’ liturgies of self-reliance, I spent more than three decades feeling vaguely guilty over the ease of my life. Eddie Rickenbacker, already a champion motor racer, shot down 26 Fokkers from the cockpits of primordial combat aircraft before he turned 30. Elsewhere on the Continent, Ernest Hemingway thrashed ambulances across the Italian Alps and posted his stories home. When would I be called on to face down fascists, rescue the tumbled victims of Nature’s fury or fight my way into the longshoreman’s union?

The first order of business was to get the hell out of Portland. The Pacific Northwest, for all I knew, was full of little but oddly polite hippies, filbert trees and damp kids wearing clotted down jackets and waffle stompers. Nothing ever happened in Oregon, especially not in my family.

Apparently, I wasn’t paying close attention.

Bumbling through a myopic childhood, painfully shy and bookish, I felt the doom of middle age early. In my daydreams, I shot down whole flying circuses of Fokkers with my Spad, always with a chivalrous wave of my gauntleted hand. Gazing into the mesmeric pictures of Dad flying AT-6 Texans along the hallway wall of his divorcee’s condo, I practiced the motions of stick and rudder, digested a hundred aircraft nomenclatures and committed the stanzas of “High Flight” to an eidetic panel of my memory before most kids could make a decent go of the national anthem. No one ever longed more to slip the surly bonds of earth, chase the

shouting winds along and do a hundred things you have not dreamed of. When an Air Force recruiting commercial intoned those words from John G. Magee through the monophonic speakers of our cabinet-style color TV (complete with record album changer and AM tuner), I resented them for broadcasting my fantasies to louche civilian poseurs in prime time. Just a chubby, four-eyed kid, I fattened glossily on jaunty dreams of gallant pursuit.

At my grandparents’ house, though, nobody cared for dashing pilots, especially the one they were convinced had stolen their fine daughter. Everybody assured me I was “just like your grandfather.”

This terrified me.

John Nicholas Fax, the grandfather of reference, was a bookkeeper in federal service, broad across his rounded shoulders and fully six-foot-three when he unfolded from his bookkeeper’s stoop. He wore heavy-framed glasses, and his only significant hair was a mustache that had last been cool in the Roaring Twenties. Grandpa was carefully polite, wore pork pie hats and Windsor-knotted ties, and insisted we didn’t disrespect Mom at any time.

I damn sure didn’t want to be Grandpa. I wanted to be Dad.

Decades later, after the stories had accumulated and taken root in my head, I realized the man my grandfather had been.

Grandpa never went to war, and I secretly despised him for that. During World War II, his brother George ran the ranch and his brother Fred hop-scotched across the Pacific alongside the Marines with the Navy’s fighting engineers, the SeaBees. Grandpa stayed safely in Milwaukie with his family, where he counted ration coupons, blacked out the windows and occasionally ran through the woods shooting roman candles at his fellow National Guardsmen. A callow kid didn’t understand quadruple deferments for having a wife and children, for flat feet and intense myopia, for having a brother in combat—or for having a strategically important job with the Army Corps of Engineers. A kid like me, brimming with the self-importance of being “special,” didn’t understand much at all.

He never fought a man with his fists that I know of, but at seventeen, John Fax’s appendix burst while he worked in the family wheat field on a hundred-degree day in The Dalles. Nobody knows how long he worked with the rupture until he passed out and was rushed to an early-century hospital for emergency surgery. They do know how long it was before he was working again. In two weeks, big John was back on the harvest. He should have died but there was too much to do, so he picked up his scythe and went back to work.

Grandpa really had been the kid who wouldn’t give up.

In his late sixties, fully retired and with all his kids raised and married off at least once, Gramps finally had a chance to go and finish the college degree he’d always wanted. Portland State University granted his BA in History—with honors—at an age when less durable men can barely parse the TV Guide.

We ate a lot of dinners at our grandparents’ house when we were kids. After watching him put away enough chow for three ordinary men, my little brother and I would descend to the basement and take turns attacking Grandpa’s prowess at table tennis. He barely fit behind the table, but Gramps was a ping-pong playing machine. Charitably, he would play us left-handed and try not to embarrass us overmuch.

Until his late seventies, Grandpa replaced a few shingles on their house every year, picked figs and plums from the tall, mature fruit trees in his orchard, and cut cord after cord of firewood. Finally, he fell out of the tree or off the roof one too many times, and once even down the basement stairs. After Grandma found him lying by the ping-pong table, she took away his chainsaw and set high places off-limits. Turned out his balance had gone off years before, but Grandpa didn’t want to bother anyone.

The big old Swede just adapted. If sometimes he fell, it wasn’t worth making a fuss about. He just got up and took another step.

Once I asked Grandma what she’d seen in Grandpa, expecting a simple confirmation that he’d been a good man; that he was reliable and stoic. That was all I knew about him. It pulled me up short when she put her hand to her throat and a dreamy look glazed her eyes. Grandma was looking back across time when she said, “Oh.

“He just looked so handsome on his horse.”

I’d never pictured him steering anything but a Chrysler.

By the time I was enough over being a tough guy to talk to Grandpa quietly, as men, he was too far gone to track our conversations. By the time Grandma had undergone her series of strokes, retreated inside herself and finally, softly died, Grandpa was well down the path of what my M.D. uncle unsentimentally termed “squash rot.” They had taken care of each other’s business for seven very full decades, and he just didn’t have anything left to do.

Grandpa’s was a quiet dementia. He cleaned his plate as always, did everything that was asked of him, and smiled vaguely when Mom barbered the Cromwellian fringe of hair on his enormous head and trimmed his pencil-thin mustache. He still didn’t care to be a bother.

All through my youth, Dad bought a new company car every two or three years, and once presented his church of the month with a new pulpit in a splashy bit of weekend hoopla.

Only during his funeral did I learn that Grandpa, humble civil servant that he was, had endowed an entire wing of the Milwaukie Episcopal Church, where he’d been a member, elder and treasurer for over 60 years. The reverend spoke of his “towering contributions to the spiritual life of this community.”

Despite my mother and aunt’s assurances that you didn’t want to be anywhere near Grandpa’s tone-deaf bellowing during the hymns, I felt cheated. I’d only heard him pray over holiday meals. I’d judged his financial acumen by the cars he bought new, then carefully drove for fifteen years each. I grew up in the shade of a quiet giant, and I never even saw him.

And I never did beat that old man at ping-pong.

————————–

2003

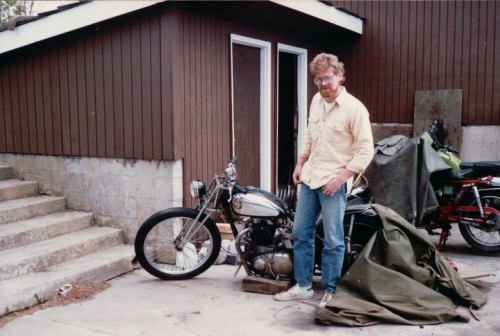

By the time Grandpa died, I was on my second wife and dozenth motorcycle.

I was a licensed pilot, a certified SCUBA diver, a Washington electrical administrator. I could drive any vehicle designed by humans. There were bolts in my leg and scars on my face. I had buried a daughter, a couple of friends, and an intended father-in-law. I’d written for newspapers, testified at a murder trial, managed a hotel and designed municipal fiber optic LANs. I’d pulled people out of cars rolled into bar pits, jumped into turnouts when the fire bell went off, and ridden horseback search and rescue missions into the Frank Church Wilderness Area.

My Rolodex, buried in a box somewhere, had numbers for dozens of attorneys and engineers and architects—even a couple of movie producers. There were stale journalism awards in one drawer, old arraignments in another and a master’s degree high up on a shelf somewhere.

Having visited a dozen distant lands and better than half the states, somehow avoiding both Mexico and Alaska, I’d ended up living less than 200 miles from the room in Emmanuel Hospital where I was born.

These and other endeavors, faux outrage, cheap idealism, bad choices and worse temper had built a life I never expected. I had matured into a broke-down army vet with a choppy resume, driving my old truck to an entry-level job.

I was Jack, of all trades.

Clearly the master of none, I still waited for that hour of need.

to be continued

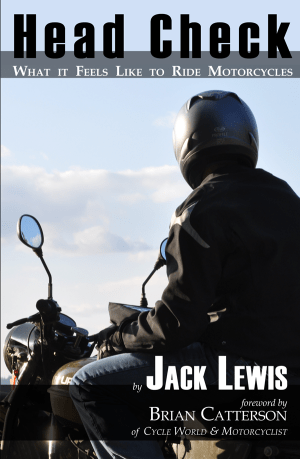

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Jack, you have one thing that I so desperately wish that I had. Ties. You have a continuing history that connects you with your family. You’re a lucky man, man. Thanks for sharing.

My Friend, you have met and stepped up in that hour of need more than once. And will again. And again.

Yes.

I could feel your true felt emotion.

It’s tough exposing the heart, eh?

Very well done, Jack.

“To be continued,” indeed.

Damn blurry monitor!

Gonna make it hard to read the next chapters, but I sure do look forward to them!

Thanks, folks. It gets… weirder… after this part.

Jack, I’ve read your drivel in periodicals for years. I even read your book. I met you briefly at DPK’s memorial. I wish I knew you better. You write real good.

Keep at it!