I woke up happy this morning, secure on a sunny summer morning as a citizen of the world’s sole superpower, next to my sweet wife. We were thinking about a little shakedown trip on the bikes. Pretty Wife’s little BMW has new shoes, and my ankle and knee are still unsteady, but the prospect of a short hop around the neighborhood made me smile.

Off to coffee, then, and a quick peek at our world through the Interlens. I was sitting there, sipping away, when the war came home again.

They’ll do that, the wars.

A friend sent me this YouTube link, a thoughtful song by Eddie Vedder. My buddy Mike, a veteran of the Marines and army, is no crybaby but he’s not blind, either.

Mike commented, “I can’t help but associate this song with a generation of men and women who will, on some level, remain removed from the same society that they sacrificed themselves for… most for the rest of their days.”

I had a team sergeant when I re-entered the Reserves. Jason was fit, early 30s, ebullient, and amazing in the woods. Blond, blue-eyed and Teutonically tall, he claimed Native American quarter-blood, though I always suspected he just liked rockin’ a fauxhawk.

I liked serving with Jason. We had a fun team, two TOFFs (“tired old fat fuckers,” my acronym for 40-y.o. reentry E4s) and a butt-kickin’ former Civil Affairs guy, all of us growed-up enough to get the joke.

At Fort Lewis, we laid hasty ambushes for our training NCO. At Camp Dawson, we got a guy captured, then traced his chatty GPS to kill all his captors with our badass blank rounds. It was great sport. We were laying in the grass, running through the woods, draining suds at the NCO club. Our whole team made the commandant’s list, and it was all so much more relaxed and fun than I remembered it from when I was a serious 19-y.o. private who was such a tightass that he once called himself in to the Provost Marshal for talking about artillery off-post while drunk (the desk sergeant gently explained that the unclassified range of a rocket remained unclassified, and that I should probably find a ride back to the barracks as they were running DWI checkpoints that night).

Jason had deployed to Kosovo, and we talked about that some. Those were the times when his faced tightened up; his teeth clamped together with the strain of trying to meter his anger out slowly. When Jason talked about his captain bailing out on him to leave him alone in a restaurant, sitting at a table with a Muslim terrorist who trained in our own Ranger battalions… that was when Jason’s hands shook. He knew nobody would understand that visceral fear and rage back in this world, not even the men and women in his Day-Glo optimistic CA unit where for drill after drill he had stalked around wanting to smack everyone he saw until finally he hit the red button and unassed for our psychological operations unit.

“It gets in your blood, you know?,” he said to me once and I did know.

Ernest Hemingway wrote, in A Farewell to Arms, ““In civilian clothes I felt like a masquerader. I had been in uniform a long time and I missed the feeling of being held by your clothes.”

“Yeah, man,” I said to Jason, “I know.”

The day I got my new gear issue, I sat on the front porch of my wife’s house, lacing up my new boots, layered in the mothball funk of new “b’doos” until I felt it all infusing me with soldierhood, jacking my spine straighter and reminding me of that tall heel military strut that I never remembered I missed except in those dreams I had sometimes, those dreams where they all marched away without me and I had no mission, no purpose, no pride.

Jason was a good man, a seasoned union carpenter, impulsive and thoughtful all at once. He got himself a huge tattoo over both shoulder blades, but it was no Fayetteville parachute or heart o’ mom. Jason drew himself a tat that showed, in fully accented chiaroscuro, Hemingway Himself locked in an arm wrestling match with Charles Bukowski.

Hemingway’s eyes bulged in grim determination. Buk was laughing. Jason ETSed not too long after our West Virginia re-class training.

“If I keep on doing this,” he told me, “I won’t be able to stop.

“At some point, I’ll be a soldier and nothing else. And then I’ll never be anything else.”

Two days ago, my friend posted a note about her cousin. Kathie’s a lifelong pacifist, but he was something other than that. Her cousin was a sailor with SEAL Team Six, not one of the famous anonymous men who shot our nemesis in the eye but a man riding to the rescue of a pinned-down Ranger unit, somewhere in the endless, timeless, dauntless mountains of Afghanistan. One of the men shot down. A soldier who now, certainly, will never be anything else.

Where do all the good men go? Some down in flames. Why him and not me? Chance, and only that. His skills exceeded mine. It is not about that, almost ever, though we all once thought it would be. Accountability in the military means total responsibility for completing your mission. There are no excuses. You keep going until you’re dead.

Come home with your shield, or on it. But some many-many of us came home and dropped our armor in the supply room. Have we shamed you? Have we become you, again, soft and placid as once we were?

Can we?

Like a shit-stained boomerang, the war comes home. We prefer not to notice. We’d rather that girl back there catch it. “Not mine,” we think about her thousands of cousins, silently thanking G-D or fate or happenstance that the boomerang is not ours to catch, not this week; even as our markets melt and our public servants are crushed and our 401(k) money fuels offshore accounts for criminals instead of funding our retirements, we can look away if we’re determined enough. It’s not our turn.

In training, we sang about it not being our turn yet. MP, MP, don’t arrest me! Arrest that captain behind the tree…

It was her cousin’s turn. Tough luck, man.

Sean, a retired Marine and the least fey poet walking around today, also emailed me this morning. His son is in Iraq now, serving with a super-secret-squirrel forward M.I. unit. Infantry training lasts 13 weeks and military intelligence training goes 20, but Brendan trained at Fort Huachuca and then at an Air Force base and then at JBLM for two solid years before he deployed. With a young, pretty wife and a passel of kids, Brendan marched off to war with a full heart and the arms of a wrestler.

I remember what that felt like. I remember the ascendant joy of feeling again, on the cusp of middle age, like it was my appointed duty to save the world: a place to apply ego and effort and pride and discipline, shoulder to the wheel in the ultimate no-whiners zone, the kind of place where NFL stars fall as fast as soda jerks from Des Moines. In the lyrics of Billy Joel, “our arms were heavy but our bellies were tight.”

Sean is proud of his boy. He’s scared for him. We’re older now, Sean and I. We can be afraid sometimes. We can be sad. We have time and space to cry like babies, now. We don’t have to hold it together all the time to make sure our guys don’t lose it under fire.

“He sent me a letter that broke my heart,” Sean wrote of his brash, grinning sergeant of a son. “He’s finally getting a full dose of Fuck from this war and his Mission: I was wondering when it’d hit him.

“Well it’s hit him, and hard.”

The war comes back, stumbling off a plane shivering, wrapped in smallpox blankets. The war comes back, alien and threatening, stuffed into our guts for as long as we can hold it until we break open and hurt someone — most often ourselves.

Discipline and duty die hard and often alone. Our national suicide rate started climbing in 2007, with the economy souring fast. It’s higher now than then, higher now than it’s been in decades. The Depression That Dare Not Speak Its Name reaps its share as people fall off the edge of even pretending they have “economic respectability,” as they are told by the very politicians who paid off Goldman Sachs with our money that it’s their own damned feckless fault and they should by G-D get a job (maybe in Pakistan, where jobs and U.S. government aid can still be obtained). Yet even amid this American epidemic of self-termination, the suicide rate among service members surpassed the civilian sector for the first time in history.

A retired army colonel, now a veterinarian of cats, called his tour as a medic in Vietnam “my year of living in Technicolor.” Combat is epic and vivid beyond all imagining, easily as addictive as it is horrifying. Like all addictions, it carries costs. One of those costs (like many addictions — surely those related to drugs, less so those concerning oil and fatted privilege) is a kind of two-way shunning: those huddling in the warm crowd push out those at the edges even as the edge walkers themselves diverge further and further from the thrumming hive.

Michael Poggi, who served as an ambush hunter with 1st MARDIV, started his story in Operation Homecoming with, “I’ve been drinking steadily since getting back from the war.”

“I hate crowds,” Poggi’s semi-fictional speaker continues, “maybe because I am hung over, or maybe because they make me a critic of all humankind. I just can’t help but think people are spoiled lambs walking around with their heads up their hinds, oblivious to the goings-on of the world.

“It makes me so damn sad.”

I remember that, too. I remember feeling like the home folk wanted just a little nugget, easily digested into a bumper sticker turd. Either “Support the Troops” or “No Blood For Oil” were sound-bite supportable.

Like sausage-making, sound bite production ain’t that pretty up close. We sat in a bunker once, Chris and I, nursing at the NIPRNET to watch a very excited MSNBC reporter explain that he was standing right that very minute on Route Irish, the main vein to Baghdad’s Green Zone, which he breathlessly described as “the most dangerous road in Iraq, where there’s an IED attack every day.”

G-D, we laughed hard then. Both Chris and I had been boomed within the previous week, twice in a day at one point. Route Tampa around the north edge of Tal ‘Afar may not have been the most dangerous road in Iraq, but the squadron we supported was finding five IEDs a day along the same two kilometers of Tampa, usually by running over them. We laughed until we had to wipe tears out of our eyes, and that’s when we should have known that we weren’t them anymore, but someone else now.

People back home wouldn’t think this shit was funny.

The war comes home napping under bridges, standing off the cops, seeping under the door while we sleep until we wake to find it staring out of the warm eye of a laptop.

I can’t tell you how or even why I miss this thing I hate, this role for which I’m customized and purpose-built. I can’t tell Brendan how to be you again, how to be cheerful and optimistic and ass-kickingly American like he was. It’s all up in him now, like it is with me and Mike and Poggi and Jason and Sam.

The war comes home like a virus that you can’t wash off or disinfect or get out of your clothes. The war comes home and kills you a little as it dies at your feet. The war comes home, an evil orphan that you may not turn away.

Becoming what you needed, we can’t be what we were. You appointed us your blue-collar champions and sent us off to kill your fears. We hunted them down until they became part of us.

You were pleased enough then to dispatch who we were. Will you not welcome what we are now? You’ve no choice, really.

I’ll try to help explain it to Brendan, and the people like him. Like us. Like… me.

For those who are not us, all I can offer is this reminder:

The war comes home.

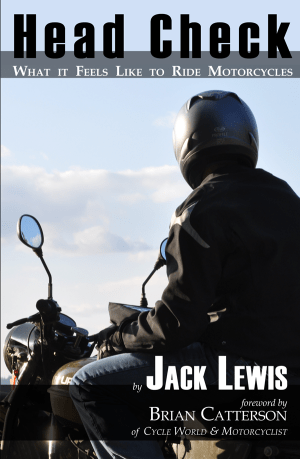

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

The war comes home, and this civilian patriot will damn well welcome the soldiers and the wives and the daughters into his own home, and feed them dinner, and lament when their plans get spoiled, and cheer them on when the bank tells them they can finally knock it off and go have FUN for a bit.

It’s the least payment I can make in thanks for your blood, toil, tears, and sweat. (And some damn fine stories, and some damn fine sesame bread, too.)

Jack,

Thank you.

Excellent. I’m still here but I do believe my feeble mind checked out some time back.

Thanks Jack.

Thanks Jack, I am glad I was able to offer a little inspiration. The MT ARNG saw fit to let my old ass back in, again. One more deployment looks to be in my future.

Thanks bro. Well said. “All gave some, some gave all.” The weight of that phrase is lost on too many.

And we never come home….we have change, they have changed, the best we can hope for is a chance to start over.

We don’t always get that chance, for one reason or another.