Nicholas and Johnny Fax weren’t the best miners who ever dug into a claim. Ambitious fortune hunters locked into the boom and bust of the Klondike Stampede, they’d spike rails for a season or two in the dry dust of Wasco County, Oregon, get grubstakes together and head north to the Yukon.

Heading out on the Chilkoot Trail. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The first time they did this, they lost it all. No easy money jumped out of Eldorado Creek (its name freshly enhanced from “Rabbit Creek”), and they ran out of cash and supplies before they could tease out enough shiny, hard assets to keep their operation going.

So they did what any real American might do: retreated to The Dalles, then known as “the biggest little city in the West.”

Wasco County, OR. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Signing onto another railroad crew, they sweated up a second grubstake. Sleeping rough, they worked like coolies and forewent any comforts that cost money. With their other brother, Mathias, they grew vegetables at a farm on Mill Creek.

In the big town of Portland, they sat for and passed their naturalization exam, becoming newly minted citizens of the United States of America, and shopped the miners’ supply houses again. The day came when they had enough in their poke to return to the great, white north, this time with their Italian buddy, Pinney.

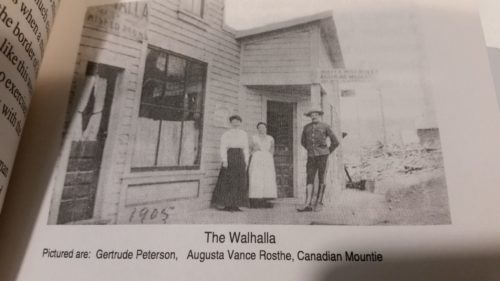

My great-grandmother, her aunt, and a hopeful Mountie. Image from “Walhalla: a Family History” by Ed Nelson with Fred Fax.

And to lose their ass, again. My great-grandfather and Großonkel Johnny went bust twice in the Yukon and once on the beach of Nome, Alaska.

Exciting as its prospects were, mining wasn’t a skill the brothers were raised on. Back in the old country, their family had farmed and milled grain. One of the reasons Nick left home early was that he’d never owned a pair of adult shoes he didn’t make himself; despite standing about five-foot-nine, his feet clocked in at size 13, triple narrow. Nicholas had shipped to America seeking ready availability of what he always called “canoe boats” to cover his feet.

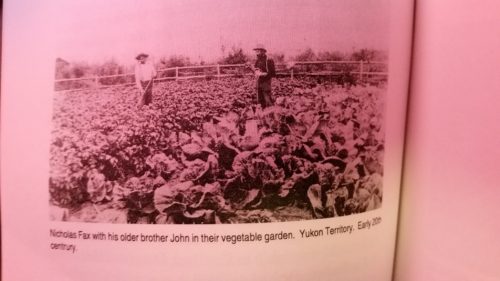

After their last mining bust, they didn’t come “home” to Oregon. Their home was in their worn, tramping, extra-long and narrow mukluks. Resolving to make their northern fortunes one way or the other, the brothers first broke ground in the Yukon with hand-drawn ploughs, quickly discovering that the endless summer days helped gardens explode with enormous vegetables. Stowed in permafrost root cellars, Fax-grown produce was readied for shipment to Dawson, filling out the grubstakes required of miners moving into the frontier gold fields.

Star-crossed miners but excellent farmers, the brothers earned more reliable income from golden squashes than they ever had from gold dust.

John and Nicholas Fax, making it big by prospecting dirt. Image from “Walhalla: a Family History,” by Ed Nelson with Fred Fax, copyright 1998.

Whether mining or farming, they had plenty of adventures along the way. They ran rivers on bank-built cargo rafts, brushed off threats from the Soapy Smith Gang, and shot wolf and bear to insulate their clothing. The Wild West had emigrated to the Far North.

The new century was barely kindergarten age when Nicholas set his eye on a real, flesh-and-blood future. While dropping off produce at the Walhalla rooming house in Grand Forks, Nicholas was taken by the tall, teenaged, Swedish hostel manager who regularly found herself surrounded by admiring Mounties on extended lunch breaks. Gertrude Petersson, niece of Walhalla’s Swedish owner and her Norwegian husband, would become my great-grandmother.

Gertrude was a multilingual international traveler and accomplished pioneer woman on the day she accepted Nick’s proposal. She was also 15 years old. At the debut of the 20th Century, Viking girls became women when they damn well felt like it.

Striking it big was no longer the goal. Work favored their prepared minds better than fortune ever had. Their plan magnified and transformed: to buy Oregon land and grow the world’s finest wheat. They were building their grubstake in reverse even as Gertrude made her way back to her own family farm in Småland to secure parental permission to marry, as mandatory for her sense of propriety as confirmation in the Lutheran church.

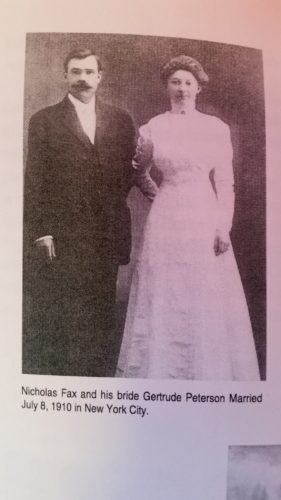

By the time she debarked from a steamship in New York City, Nick was waiting at the gangplank with a platinum-bodied diamond engagement ring from Tiffany’s, size eight and a half. Gertrude may have been a quiet young woman, but she was neither shy nor tiny. She looked her husband straight in the eye, though she did have shorter feet.

Nicholas and John weren’t shy, either. With savings from farming the Yukon, they bought the old Rice place and bent the rolling hills of eastern Oregon to their will with innovation and resolve.

Growing wheat on the old Rice place. Photo courtesy of Off The Grid News.

Contour farming? They were all over that. Crop rotation and fallowing were old news to them. They bought and deployed the first power tractor to pull a combine in Wasco County, retiring their tack and draft horses.

John bought a Model T Ford and quickly earned his reputation as a ditch bomber, reminding his children after each fender-wrinkling biff, “Donchoo tell yer Motter!”

Those funny-talking Faxes became grange members, volunteer firefighters, church deacons, hospital donors, and charter members of the Old Wasco County Pioneers. They lent their hands to barn raisings, shot pheasants in the draws, and fished Fifteen Mile Creek where it ran along their property. You can still drive Fax Road through there, if your truck is sturdy or your car is old.

Perhaps it will always be called that, but it almost wasn’t. For all their capabilities, one thing those Fax brothers never learned to do was speak English without an accent. Separated from the Nazi  fatherland by a bridge over the Moselle River, native Luxembourgers speak French, German, and their own national patois. Swedes speak Swedish. Their homestead rang with hard consonants and glottal spit, drifts of verbs piling up against sentence ends. To ken an approximate audial notion of their spoken English, imagine a platoon of enthusiastic Yiddish Yodas.

fatherland by a bridge over the Moselle River, native Luxembourgers speak French, German, and their own national patois. Swedes speak Swedish. Their homestead rang with hard consonants and glottal spit, drifts of verbs piling up against sentence ends. To ken an approximate audial notion of their spoken English, imagine a platoon of enthusiastic Yiddish Yodas.

By the time World War II darkened Europe’s horizon, the Faxes were pillars of their rural township. Of the three sons they’d raised, my grandpa John kept books for the Army Corps of Engineers and was considered a strategic employee for national defense; Fred joined the U.S. Navy, volunteered for Seabee training and fought Japanese expeditionary troops across the Pacific; George, the youngest, stayed to raise grain for Uncle Sam’s provisioning.

The Faxes talked funny, though. They cherished a few odd, imported habits. And, as bona fide millionaires in an era when that meant something more than “a bank manager who invested prudently,” some of their pioneering American neighbors felt my forebears had risen above their immigrant station.

There were mutterings. Neighbors who’d stood red-cheeked and smiling in my great-grandfather’s living room, discussing crop futures and drinking his holiday wassail, started side-eyeing them in church. Inferior hands who’d been kicked out of the bunkhouse for drunkenness were emboldened to spread rumors. Rumor spreaders enjoyed unearned credibility by virtue of their native status, a generation or two removed from their European roots.

Let me put this fine a point on it: the forebears of some of my fellow Americans sat down in private convocations to discuss how to “take out” my forebears the moment my family full of naturalized citizens (from suspiciously northern European nations) betrayed the slightest hint of an expected disloyalty. My great uncle and great grandfather were informally targeted for assassination, “just in case.” Although my grubby immigrant antecedents produced more bushels per acre than nearby ranches, I’d like to think there wasn’t any pecuniary ambition involved.

I bet you’d like to think so, too, but we’d both be wrong. It’s always been the worst of Americans who’ve envied the best.

Still, my great-grandparents were only a little “different” and didn’t suffer overtly. If they didn’t get their accustomed premium price at the Boyd grain elevator, or received a chilly lunch service in Dufur, well… at least they weren’t Japanese.

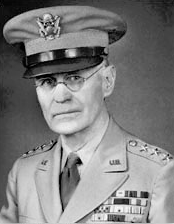

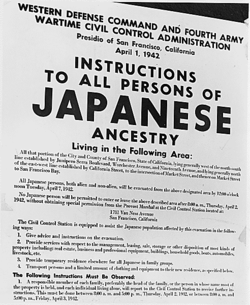

Asians had been declared “an enemy race” by an ambitious REMF general who managed to serve 49 years in the army, through two World Wars, without earning a single combat award. On General

Gen. John Lesene DeWitt. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

DeWitt’s advice, Pres. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 and DeWitt – who had previously shouted down treasonably pacific San Francisco city leaders over an 85-plane Japanese reconnaissance raid that proved as imaginary as the Bowling Green Massacre – commenced rounding up undesirables.

Japanese-Americans living near the Columbia River were suspected of plotting to blow up Bonneville Dam, turning (with apologies to Woody Guthrie) the dawn back toward darkness. Masuo Yasui of Hood River was charged with plotting to blow up the entire Panama Canal.

The great organizing principle of xenophobia reliably trumps the rights of others, and facts are extraneous to fearmongering. All Americans of Japanese extraction who lived west of Oregon 97 were rounded up for no-expense-paid tours of Idaho’s Minidoka concentration camp, where they would pay their debt to society for such un-American activities as owning a gun, taking a photograph, or being Japanese – citizen or not.

“A Jap,” quoth DeWitt, “is a Jap.”

Some 14,000 of those “Japs” joined the storied 442nd “Go For Broke” Infantry Regiment. Fighting across Italy, France, and Germany, they earned their place in America’s melting pot as the most combat-awarded unit in the long, bloody history of our army. The lowest, most disreputable private who ever mustered out of the 442nd was more highly decorated than that bitter old quartermaster, General DeWitt.

Those “Japs” also included the future father of my school chum, Hisashi. A cheerfully taciturn man who wore a battered pork pie hat, worked out of a VW pickup truck and smoked his pipe upside down in the rain, Mr. Fujinaka was the lead gardener for the Japanese garden in Portland’s Washington Park. It opened the year I turned three and, while Gen. DeWitt certainly wouldn’t have been impressed, Japan’s ambassador to the United States hailed it as “the most beautiful and authentic Japanese garden in the world outside of Japan.”

Japanese families lost their farms, their cars, their business connections, and their communities.

Japanese families lost their farms, their cars, their business connections, and their communities.

We didn’t. My Nordic relations continued with their lives as J. Edgar Hoover vacuumed up German spies from coast to coast – while not one single act of espionage or sabotage by Japanese-Americans was ever reported during World War II.

Consider that: not one. Either Japan’s generals confined their dirty pool to the Pearl Harbor attack, or Japanese-Americans remained staunchly loyal to the Stars & Stripes, even as it rippled over the prison camp gates they marched through.

Even with suspicious accents, it was good to be a white American then. Perhaps it still is. It’s certainly been working for me, and it fits right in with the autonomist fervor now sweeping the northern hemisphere: if you’re gonna be a nationalist, be a White Nationalist. Play on the winning team, am I right?

Nicholas and John went on ranching wheat, paying taxes, and supporting their community. When the United States government told them to stop farming, they left fields brown and bare. When our government demanded they grow extra wheat for transshipment to

Soviet propaganda.

the U.S.S.R., they grumbled their Republican suspicions, but complied. In due course, they left the farm to Nick’s sons – but it’s not all they left. Like your own family, they also left a big story to live up to.

Nicholas’s granddaughter grew up to marry and divorce a fighter pilot, with whom she bore four children. Those kids (I was #2) had the run of their big Portland house – but not the whole house.

Despite becoming a single parent, Mom helped our church sponsor a family of Cambodian refugees, the pater of which had been an air force colonel in his home country. He started over in Portland as a mechanic, working at that until he managed the garage that employed him. When the owner retired, Mr. Phuc bought him out.

They quickly became our excellent friends. If you’ve never been to a Cambodian heritage festival in all its shining glory, with the whirling dances and smokin’ hot, polychromatic food, you’ve missed an essential part of my American experience and I pity your lack.

Two refugees of Vietnam’s war, Lin and Pha-ie, lived with us for a few years. While I’ll never properly replicate Pha-ie’s hot pepper-fried rice, at least I have the memory of experiencing it – both the incredible, layered flavor and the eye-burning oil smoke that filled our kitchen like napalm. I would wish the same for you, especially if your own culinary heritage (like mine) suffers the horrors of lutefisk.

When the Boat People’s kids enrolled at my high school in Olympia, Washington, some of my classmates (cued by parents) needed reasons to despise the new fish, so they made one up: the higher student count bumped us up from a double-A to a triple-A sports school, dropping our baseball team from second in state to a non-contender. Everyone knew zipperheads couldn’t hang with AMERICAN sports! They were the same cool kids who whispered that our Willows Program, which mainstreamed developmentally disabled teens, created a rape risk for cheerleaders.

Meanwhile, a Korean-American sophomore quietly dominated his powerlifting weight class, eventually losing only to the smallest lifter who’d ever strutted into our weight room: an actual dwarf. And most of us eventually figured out that a hug from someone with an extra helping of 21st chromosome is a great hug, every time.

There’s an old saying that the only real blondes are dye jobs, because they’re the only women who wanted it badly enough to voluntarily join that, er… “elite” sorority. Is that true of immigrants, too? Are they better Americans than you? Better than me? Do they try harder? Do they work better, taking less for granted?

I’m still too young to answer that for you, but you can follow the question to its source. Unless you’re a full-blooded Native American, your U.S. citizenship is an unearned gift bequeathed to you by the grace of immigrant grit – just as mine is. Whether you’re the scion

Ellis Island medical check. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

of Irish cops, a Central Valley agriculturalist with a Mafia-chic surname, the descendant of slaves with a proudly Presidential surname, or a Virginia member in good standing of the Daughters of the American Revolution, your citizenship here defines you as the permanent obligor to refugees from abroad.

“Forgive us our debts,” a famous Jew once prayed, “as we forgive our debtors,” but you can forgive yourself. Reach down to find your American courage, and pay it forward into our common American future. We’re all in this together.

The tradition that made the United States of America the strongest socio-political mongrel in human history is sorely tested now. Today is when we honor our debt to the émigrés who built this country; when we satisfy – or fail – our obligation to the future.

The honest way to accomplish that necessary task isn’t with a whitewashed hagiography of “The Founders,” but by welcoming your own ancestors’ true descendants: today’s American immigrants. They will be our strength if we allow it. In a lyric lifted from Canadian singer Gordon Lightfoot, “The house you live in will never fall down / If you pity the stranger who stands at your gate.”

Your local mosque, if your community is blessed to have one, offers open houses to infidels like me. That’s how you discover which of your neighbors have mouth-watering recipes for lamb – not to mention bargains on halal butchery, if you’re of a mind to return their invitation. Like us, you may have a Buddhist temple within bicycling distance of your house – would it offend your god to light a joss stick there? Square off against the sons of slaves and drag-race your motorcycle for pinks. Buy an ill-bred dog from the Amish. Get publicly drunk at a Greek wedding.

Maybe visit a taco truck, the kind we called “roach coaches” in my army days, and eat the kind of Mexican food you just can’t source from a well-lit, plastic-trimmed, drive-through window, prepared by people who can’t logically be both “lazy” and “stealing our jobs.”

Bumping into another culture is as daunting as shipping to basic training, or your first day at a new school, and the payoff is equivalent. You’ll earn experiences to remember until your last day.

Maybe you’re stuck in the sprawling, white bread middle of the country, though. Deep within our national center of gravity, your neighborhood might just be planted square in the kind of safe-space bubble that substitutes fearful jingo and lazy prejudice for America’s deep-running traditions of valor and compassion.

Summer storm in The Dalles, Oregon. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Don’t blame yourself. My forebears got through it, and so did yours, and so can you – and I want you to. I want to be as proud of my fellow Americans as I am of my own stiff-necked, reticent, beautiful family.

I want to be proud of you because I love America, and Americans, like the third-generation anchor baby I am. Consider this: every first-generation American is a Founder of the nation we’re perpetually in the process of becoming.

There isn’t a single native-born U.S. citizen who can honestly claim they’re more patriotic than the citizens who have to fight their way in to sit for a test. Our immigrants wash up here full of piss and vinegar, as fanatically loyal to American ideals as someone who just quit smoking, or started up Cross-Fit… completely off the hook.

Looking at the facts of my life, I can rest my own confident patriotism on military service, paying taxes, community service, and founding businesses: all things that first-generation immigrants demonstrably do as well as I can, and without the head start I enjoyed. Still, I want you to be proud of me, and to make me proud of you every day that we wake up in this remarkable republic. E pluribus unum should bear currency beyond fifth grade history.

So I propose that you do as I’ve done and pay a respectful visit to the graves of your own ancestors, those truest of Americans who risked their lives and fortunes and sacred honor to come to this good place and build community from the ground up.

For me, that’s a humpbacked ridge outside The Dalles with a few scrub trees, where the bones of my intrepid grandparents and their parents and their siblings lie, and where one day I will lay my mother to rest. I may even sift into that high desert soil myself, my long, traveling feet finally quieted for good.

The wind there is constant. To those who have ears to hear, it whispers our history.

Cemetery at the old Rice place, Wasco County, OR. Copyright © 2016 Kirsty M. Haining.

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

Right on it

Jack thank you, brilliant, heartfelt, soul search, piece of work.

You sir are right. However, foolish we would be if we did not try and weed out those who would harm us and thereby destroy our ability to be the haven that this country is.

We don’t have to be fools to welcome new blood into our body politic.

Vetting immigrants is fine — and not a new idea. “Extreme vetting” is just a marketing euphemism to polish up the old tradition of scapegoating.

Of course, and let us praise the remarkable record of safety we have had. You could say it’s understandable that immigrants would have a lower rate of terrorist violence than native-born citizens — whom we don’t get to vet — but it’s still worth respecting a job done well.

Syria, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Libya and Yemen — This like TSA, is pure window-dressing with no substance; all loud political posturing and damn the consequences. No medical or humanitarian exceptions, no real thought, and no reality-testing. Get used to it.

I suppose one rationale might be that in many of these countries such chaos reigns that proper vetting is impossible. However, that wouldn’t quite fit for Iran. I’m not aware of any Iranians committing terrorist acts in the US or Europe, even though Iran as a state certainly contributes training and financing to terrorist groups as diverse as Hamas and Hezbollah. But then so do Oman and Qatar.

Actually, I’m all for thoughtful ‘actuarial’ profiling, as long as it’s real and meaningful, and all these nations would be on the list — but in terms of actual risk of terrorist acts by citizens, they’d be after Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Algeria, and Egypt, not to mention Gaza. So would British citizens age 17 to 40 of Pakistani origin, and same age French and Belgians of Algerian and Moroccan origin. Student visas from these countries would be particularly well-vetted, far more than immigrants or refugees.

But that’s if our leaders were really interested in security, not just hate-mongering and grandstanding, and since useful profiling would involve a lot of planning, research, and continuous effort, let’s just go for the bling.

“Actuarial profiling” might just be my favorite new phrase. Thanks, Pam.

Terrorism aside (though the tactic appears to be quite viable in its means) and writing merely of immigration:

If one cottens to the science of anthropological genetics and evolution then one must also except that only individuals living in Africa who can trace their ancestors back to the KhoiSan aren’t immigrants. Or so the current theory states.

And yes, that also includes “Native Americans.”

Just sayin’. ;^)

Great piece as always ! You do have a way with words. As you can see, I do not ! Please keep it coming, Thank you !

Thanks, Brother

Ah, my man, solid work again. I admire your craftsmanship serving our truth. My mom’s family traces a homogenized past back to Christopher Norton who got a discharge from Washington’s army to bring in his crops. And Dad’s grandparents came from Glasgow and Brighton, by way of Elis Island and Canada respectively. Thanks for reminding me how I got here.

ha, my grandfather born and bred a sooner had bit of a northern german accent…you know that ethnic german Russian accent. Got teased a bit for it in the second war. He crew chiefed on pretty much everything that had radial motors, spent enough time at the PBY school in Biloxi that my grandmother couldn’t stand seafood anymore (the pay was so low they really did rely on the kindness of shrimpers). I’m sure there was some sidelongs at his parents and other such relatives. Who got there section of NW Oklahoma by trading 80acres of river bottom and an old mule for it. That wasn’t much land really, not for wheat farming. Never got rich, never got hungry and it was sold of some years ago when wheat just wasn’t making a dime. And we wont discuss the maternal side but, when a man born in America has to change spelling because of discrimination, gives things a bit of context. But, yeah. I figure always give those poor suckers who worked to get her just a little more slack than I give the guy who is 7th gen and waving militia papers for one of his ancestors…I sure didn’t have to work to be an American. I do work at being a better one than I was yesterday.

Citizenship is a process, not a status.

Working at it is what counts.

Hi Jack, I really miss your writing in the motorcycle press. I don’t see your name anywhere in the “new” Motorcyclist rag. I am hoping that you will turn up soon somewhere! My interest in the mainstream Moto-mags is going downhill and I get more out of Revzilla blog than Cycle World/Motorcyclist. I like the

writing more. Please find a place to share your words. I miss them. Let me know where,and i’ll read there. Thanks for some great stories! Mark Nolan

I mostly ramble along on this blog, lately.

May need to look further afield, eh? Thanks for the encouragement, Mark.