A few minutes ago, I saw a post on Facebook from a man I respect, and was startled to realize that the events described below happened a full decade ago. I won’t ask “where did the time go?” — there are records of much of it, scattered around this very house — but will note that I’m not sure I really know the guy who wrote these words anymore, even though he has the same name as me.

The other names in this old piece of email aren’t real. I changed them years ago. “SGT Bannock” and the captain know who they are; as for “SSG Grantley,” everyone who mattered to this place and time knows who he was, and reveres his memory.

Godspeed, intel geek. You were one hell of a cavalryman.

Why I Smoke

E-mailed MAR 05, FOB Sykes, Tal’ Afar

The lunar dust of Forward Operating Base Sykes was just transitioning from a muddy, boot-gluing squish to the hard, desiccated crunch under our boots that will characterize it for the next several months. At about 75 degrees, it was about as perfect as days come, west of Mosul.

”Got your Zippo?”

“Yeah. Got one for me?”

“Yeah.” SGT Bannock shook two out, proffered one.

And we lit up, and walked under the spring sun toward the mess hall, where 300 chairs were waiting, set out in neat rows.

“What’s this, the fourth?”

“Something like that. There was SSG Simmons, and PVT Guevara, and that EOD guy, and now Grant.”

“Yeah.”

We walked another hundred meters or so.

“I don’t want to go to any more of these things.”

“Yeah, but you gotta go.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Yeah.”

We flipped our cherries into the dirt, stashing the dead butts in the cargo pockets of our DCUs.

The service was much as we remembered it, from the previous three. The colonel had all the words, none of the meaning. The chaplain didn’t miss the opportunity to describe Staff Sergeant Grantley as a “meek” man, leading into his lesson on Biblical meekness. Grant’s last hurrah was to charge down a dark wadi in the night, scanning, rushing, firing. He ran straight into an ambush, and that was too damn bad for him and maybe worse for his friends, but he was no meekling. For better or worse, Grant was a warrior.

SGT Bannock told me a story about Grant before the service. He came off as meek sometimes, with his big wire rims, just-folks demeanor and impeccable farm boy manners. Hard-guy grunts and  scouts could underestimate him. One night, on mission, he was tactically questioning a potential detainee downrange, asking those innocuous-sounding questions to which people invariably respond by lying.

scouts could underestimate him. One night, on mission, he was tactically questioning a potential detainee downrange, asking those innocuous-sounding questions to which people invariably respond by lying.

“He’s not going give you any straight answers,” quoth a cav scout. “Whyn’t you ask him where the fu—” And SSG Grantley wheeled around and put his beak straight in that soldier’s face.

“Why don’t YOU let me do my job?”

Not so meek, maybe. Just quiet, polite, confident. Very dedicated to his job which, to his mind, was stopping terror attacks.

Two days before the service, I rode with Blackjack Troop for a mission, and heard from their fire support officer how Grant held on and battled. With several gunshot wounds in him and arterial bleeding, he managed to turn on two flashlights to help others find him. Once in the Stryker, Grant bled so profusely that the fizzo would have to throw out his boots, but he held onto sweet life for 20 minutes more.

Among the officers, only Grant’s supported commander, an exceptional captain, painted a fair picture of him. Otherwise, it was just another one of those services. The squadron commander gave his standard speech (filed under “moment of public grief,” no doubt) in his standard petulant whine. When the ranking officers finished their obligatory tributes to a man they scarcely knew, his buddies took the mike, and for a moment we were shown a truer picture. Not that his buddies will write Grant’s history, or his posthumous award recommendations.

A chunk of his history is written into the soil, woven into the public fabric of Mechanicsburg, Iowa. More than two hundred townspeople visited his parents’ house within 24 hours of their notification. Had he been from Philly, or D.C., or Seattle, I wonder if there would have been twenty. There is something about having fewer total people in a place that makes each one more precious to the others, and something about masses of people that makes attrition so much less important. It is the bitter irony of cities, this isolation from your fellows.

There’s no such phenomenon on a FOB. We’re the ultimate small town, dependent on each other for much more than the occasional cup of sugar. Everyone here is like a volunteer fireman, ready to help on the instant. It’s hard to think of the guy who might drag your bleeding ass out of the kill zone as expendable. Any soldier here might have occasion to do that for you.

When the benediction was finished, the ops sergeant major started fingering soft jazz notes out of his worn guitar. We marched forward, four at a time, to pay our last respects to Staff Sergeant Grantley by saluting his cavalry Stetson, boots, spurs and weapon.

Grant was the NCOIC of a Tactical HUMINT Team (THT). His team had two women on it, and those gals didn’t get out of there without sobbing and dripping tears. But then, a lot of soldiers didn’t. The fashionable look at these events is black-tinted eye pro, accessorized with Kleenex packs.

Outside the dining facility, you could tell who had just emerged, because they weren’t talking to anyone. They were off in a corner of the blast barricades, lighting cigarettes and brushing at their eyes as though they’d gotten smoke in them.

Bannock and I found our own corner and dug out a pack of Gauloises. At seven bucks a carton, they’re cheap therapy and, judging on results, effective as the average shrink.

Grateful for the smoke in our eyes, we gave a soldier’s benediction  for a man we respected enough to trust with our lives.

for a man we respected enough to trust with our lives.

“He was a good guy.”

“Yeah.”

Most of them are.

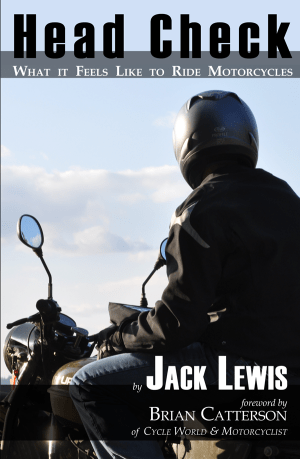

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

I like kronenbourg beer. Its yummy.